A wander into the world of Wind in the Willows

This post first appeared on Picture Book Den’s Blogspot.

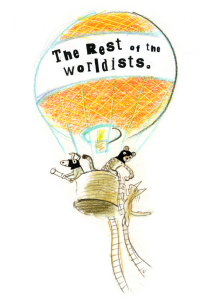

As a child I watched far too much TV. There was a show called Tales of the Riverbank. The stars of the films were real animals, who were shown moving around in miniature boats, cars, balloons and aeroplanes. I loved seeing rodents rushing downstream in rickety water-crafts.

As a child I watched far too much TV. There was a show called Tales of the Riverbank. The stars of the films were real animals, who were shown moving around in miniature boats, cars, balloons and aeroplanes. I loved seeing rodents rushing downstream in rickety water-crafts.

I live near the river in Oxford, and there’s nothing I’d be so excited to see as a water-vole rowing a tiny boat down the Thames.

I live near the river in Oxford, and there’s nothing I’d be so excited to see as a water-vole rowing a tiny boat down the Thames.

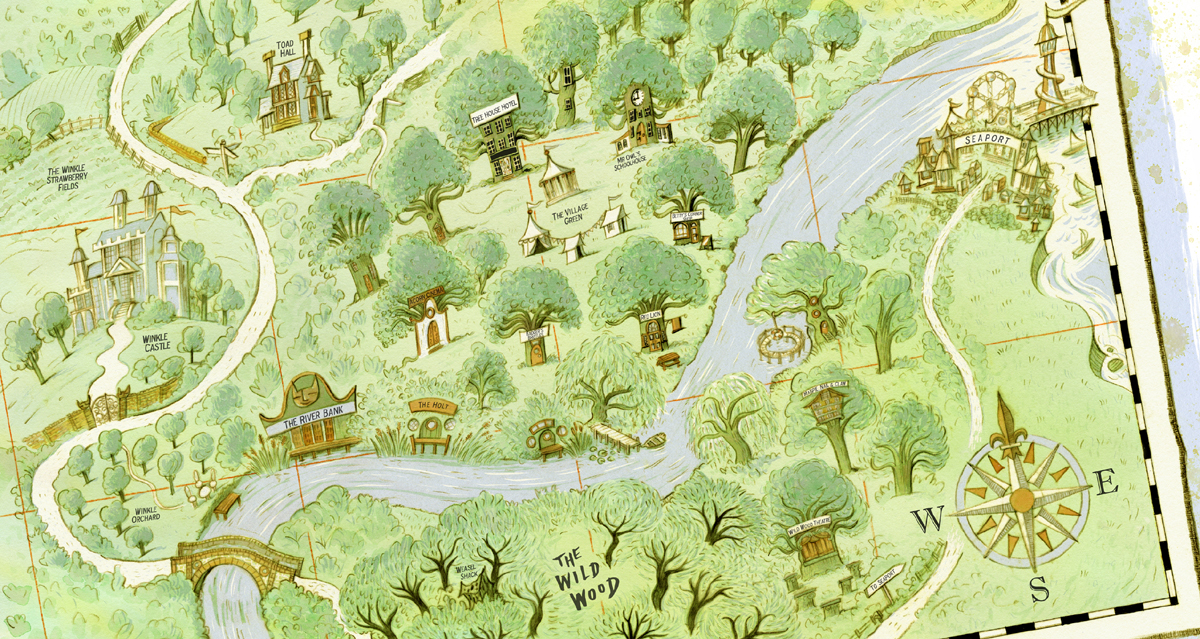

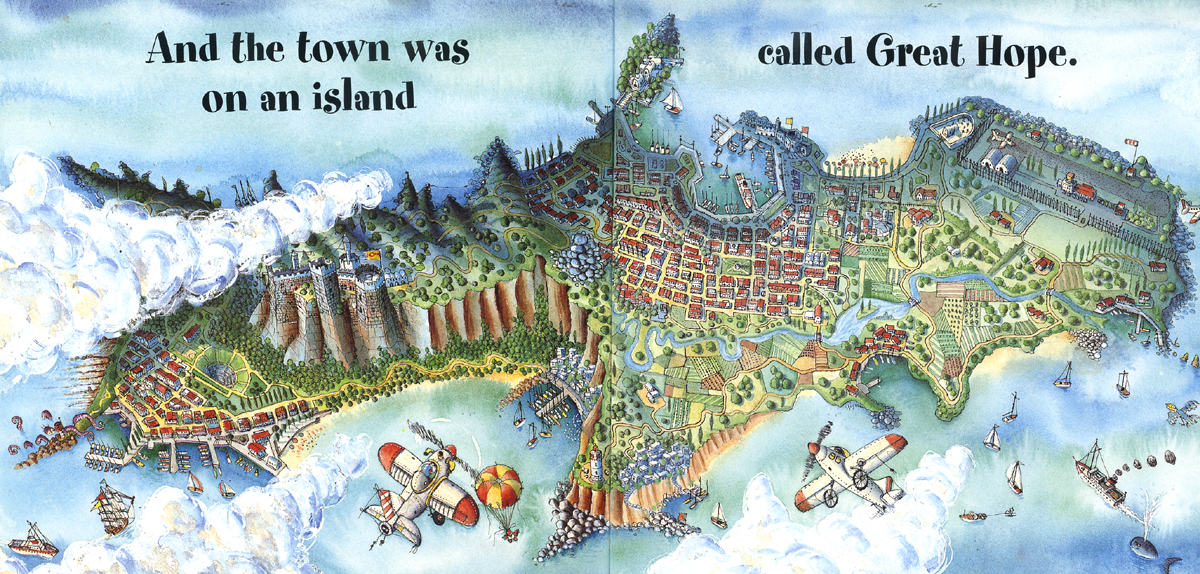

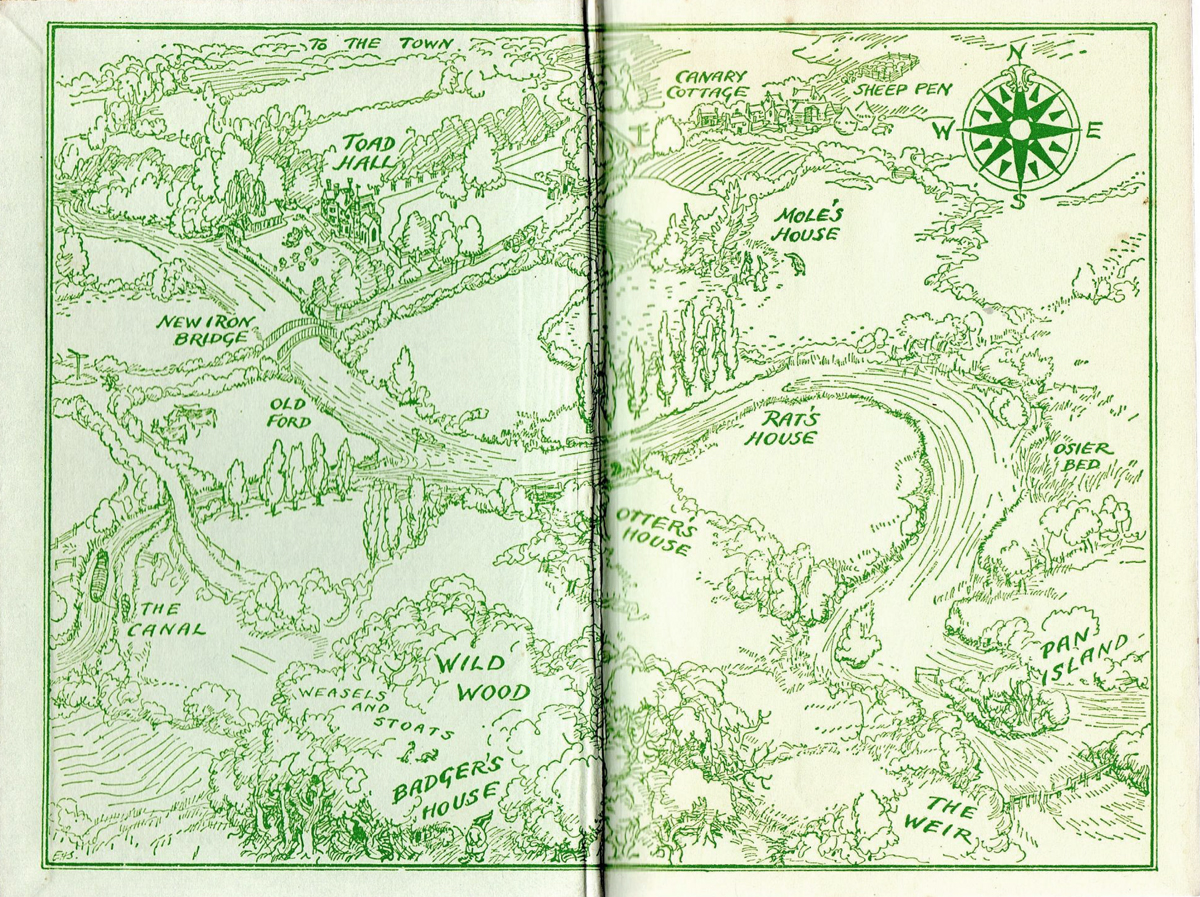

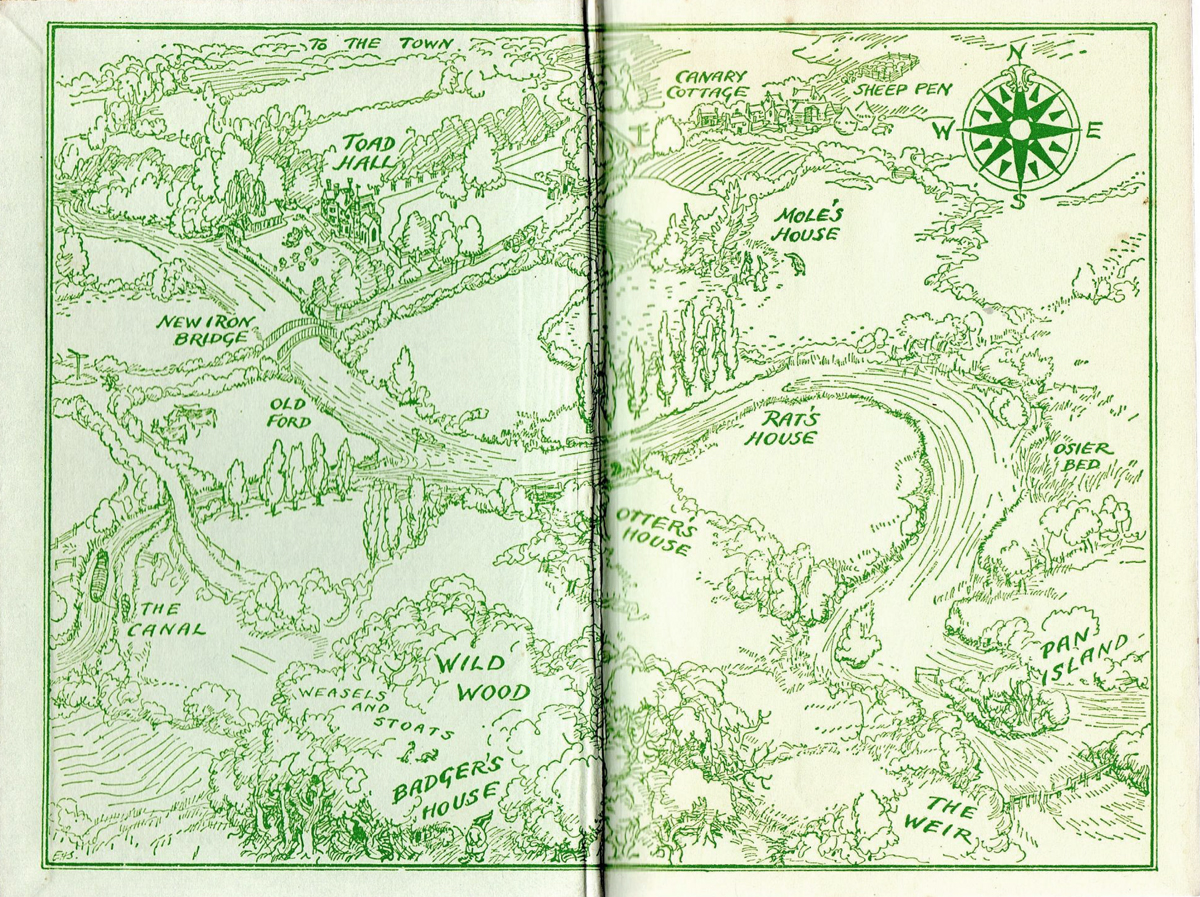

The original messing about in boats is of course in The Wind in the Willows. And I’ve recently finished making the illustrations for a story set slap-bang in Wind in the Willows territory, so in this post I’m going to have a look at Kenneth Graham’s book and some of its illustrators. I want to consider the challenges of illustrating in the Willows Zone, and how the Willows, the most comfortingly nostalgic of books, was actually shivering with premonitions of the modern world.

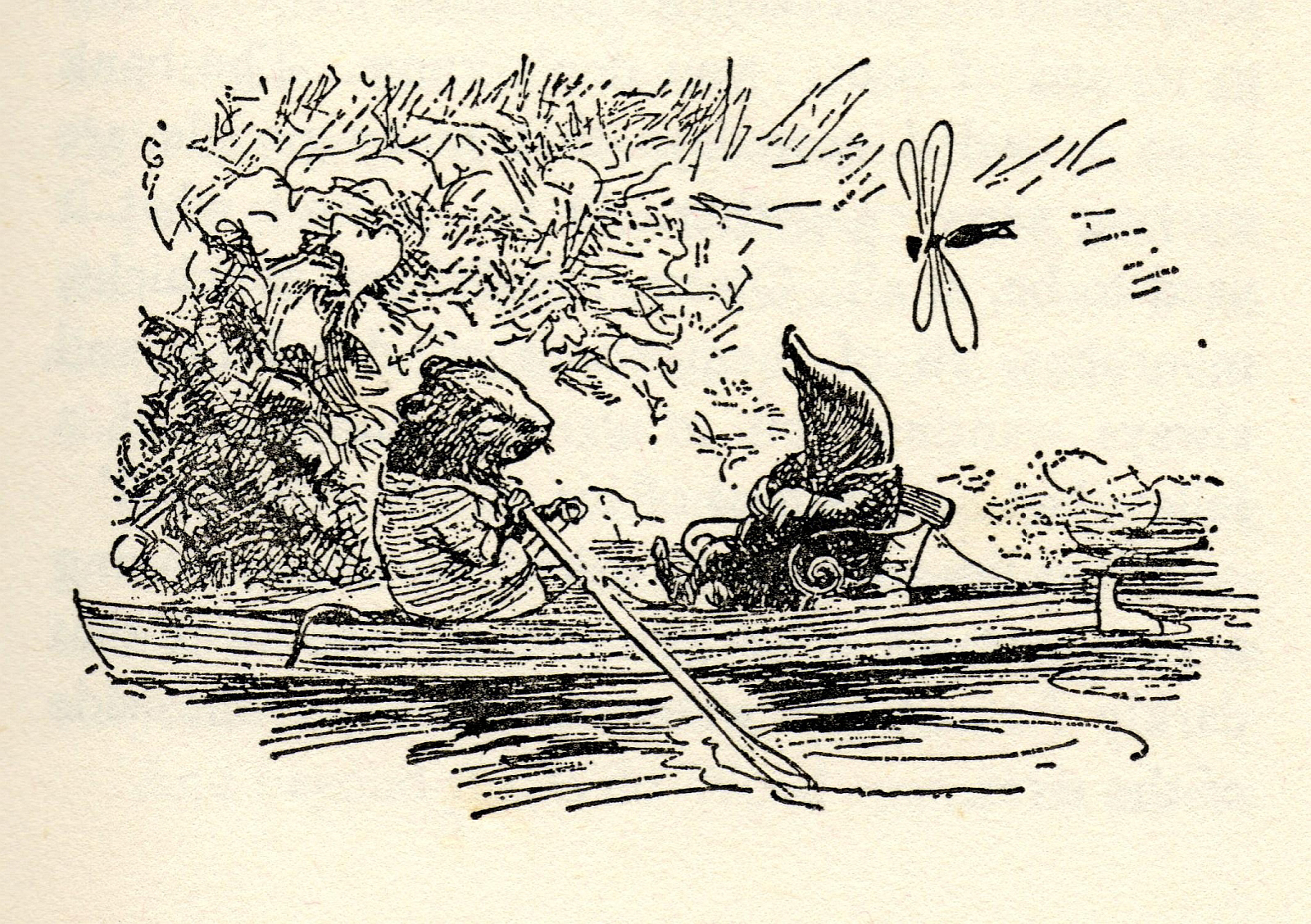

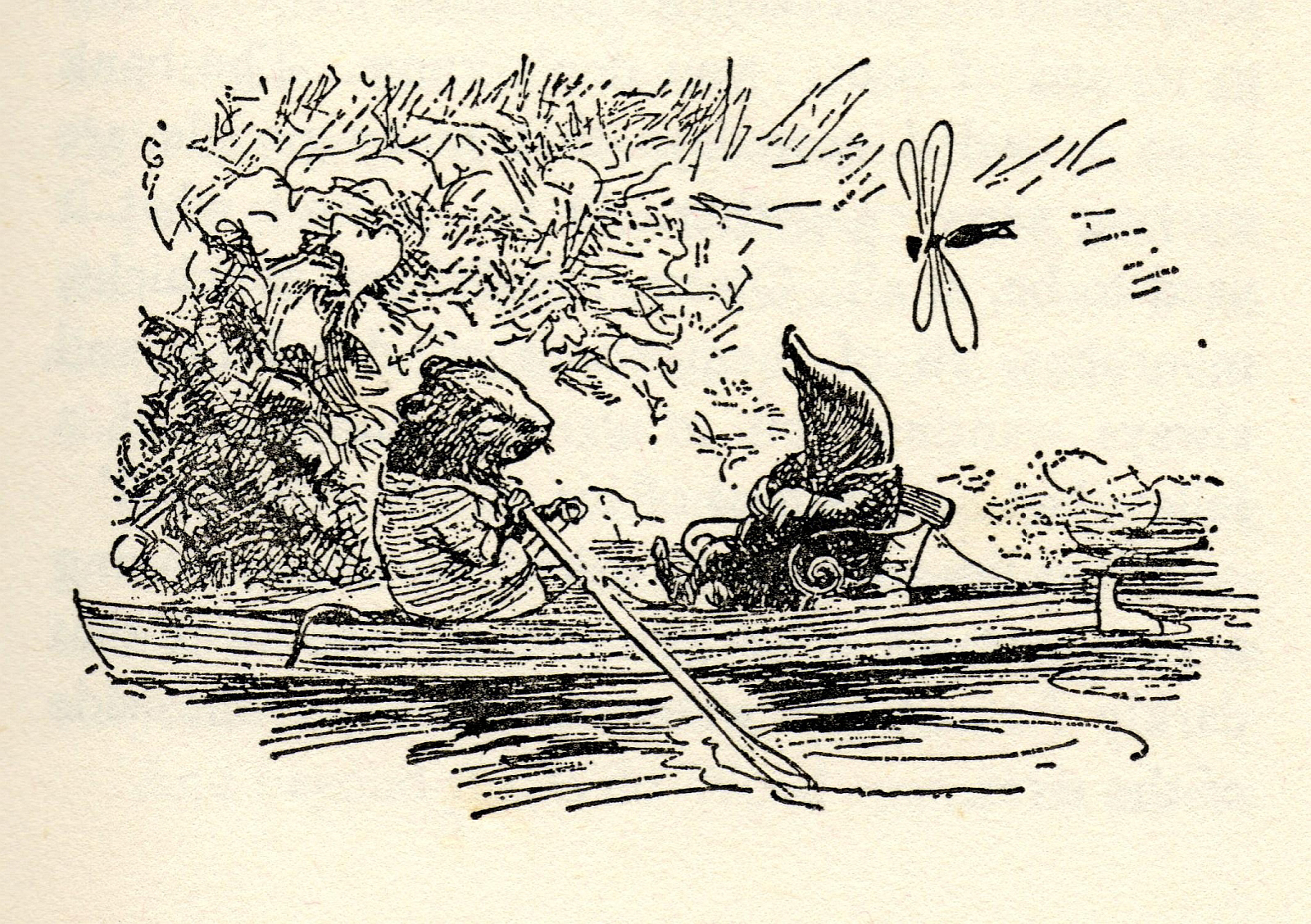

The book was published in 1908, but it wasn’t until 1931 that EH Shepard illustrated it. To me EH Shepard’s pictures are as much a part of Wind in the Willows as the text – so I was surprised to discover they weren’t there at the beginning.

Grahame didn’t live long enough to see the book released with Shepard’s illustrations, but their meeting would be reported by Shepard in a 1950s edition of the classic, as follows:

“Not sure about his new illustrator of his book, he listened patiently while I told him what I hoped to do.

Then he said ‘I love these little people, be kind to them’.

Just that; but sitting forward in his chair, resting upon the arms, his fine handsome head turned aside, looking like some ancient Viking, warming, he told me of the river nearby, of the meadows where mole broke ground that spring morning, of the banks where Rat had his house, of the pool where Otter hid, and of Wild Wood way up on the hill above the river.

…He would like, he said, to go with me to show me the river bank that he knew so well, ‘…but now I cannot walk so far and you must find your way alone’.”

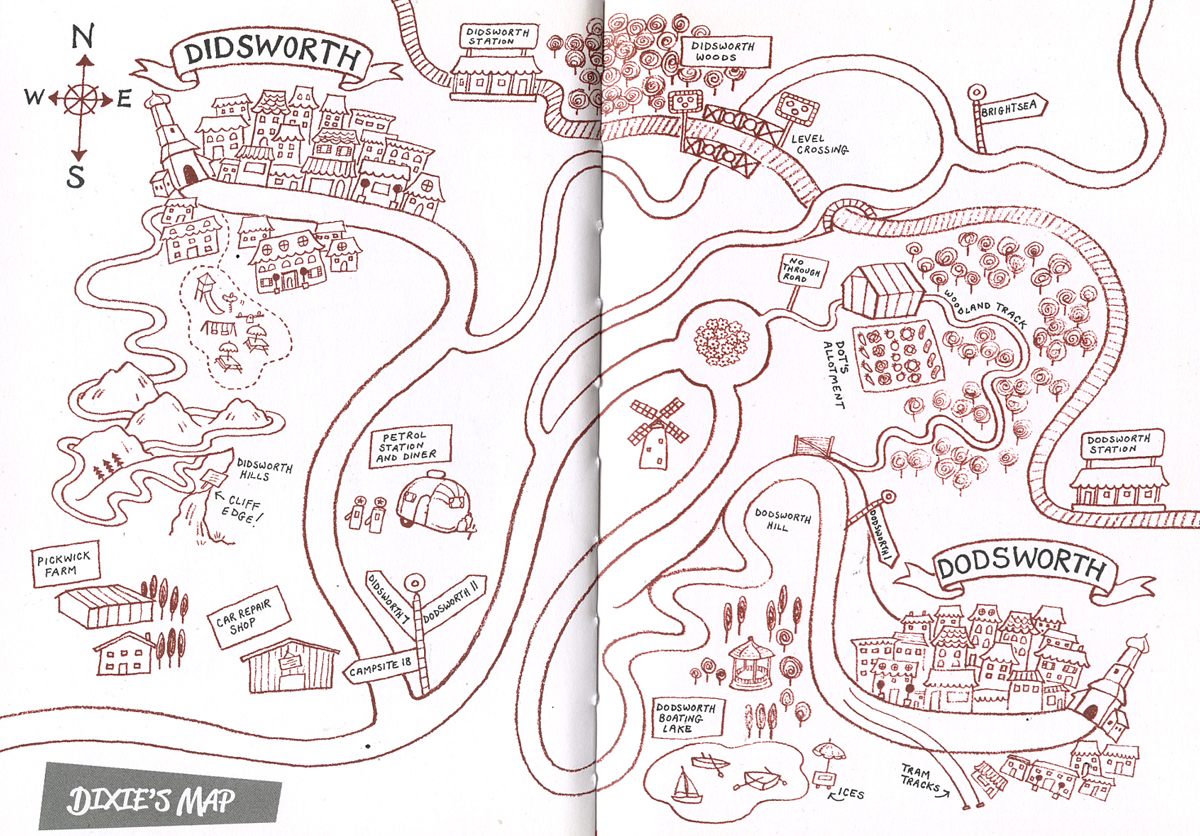

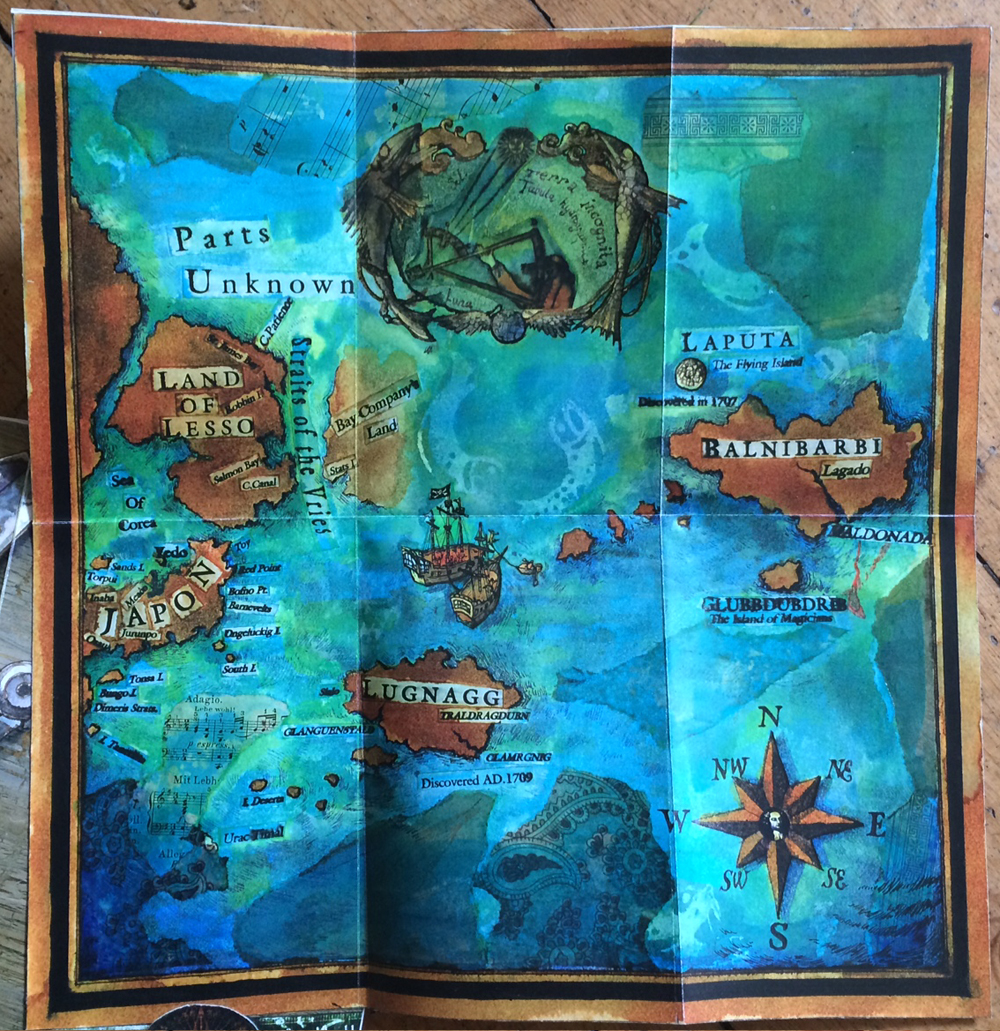

Grahame was living in Pangbourne near the Thames – and at other times he lived in Cookham, also on the River Thames – so to me, the river running through the book is always the Thames – which bubbles up in Gloucestershire and flows through Oxford, Reading, Henley and Windsor and eventually becomes the great river that snakes through London on its way to the sea. Mole, on his escape from white-washing, is captivated by the river; it “chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.”

The Wind in the Willows has been rich ground for re-illustration. To me EH Shepard’s illustrations are part of its fabric, like Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice, but still both books are big enough to inspire reinvention.

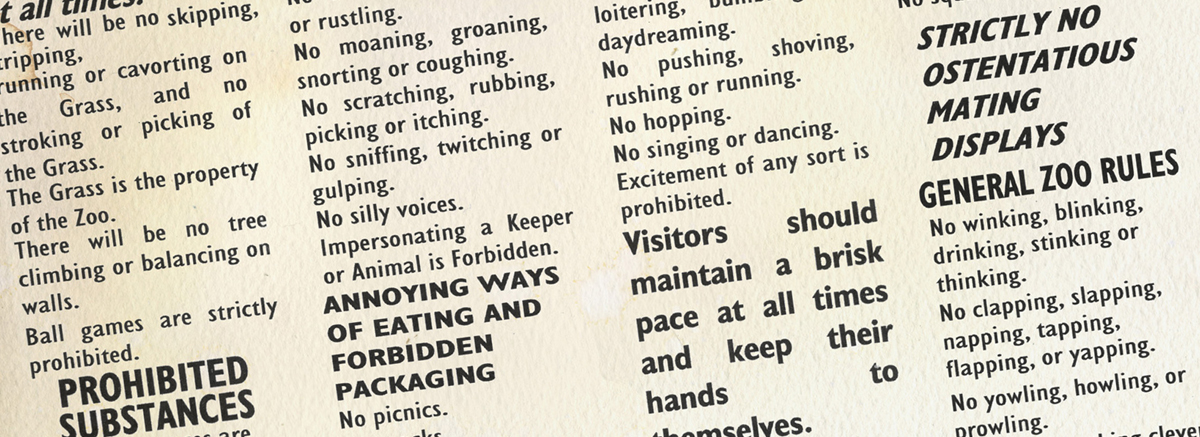

And so far, in all the versions I’ve seen, the animals are wearing clothes.

Animals in Clothes

I have love-hate feelings about dressed-up animals. I really don’t like animals that seem to have human bodies under their animal heads. But if their body-shape seems to be the stumpy innocent sort of shape of an animal, then it’s OK.

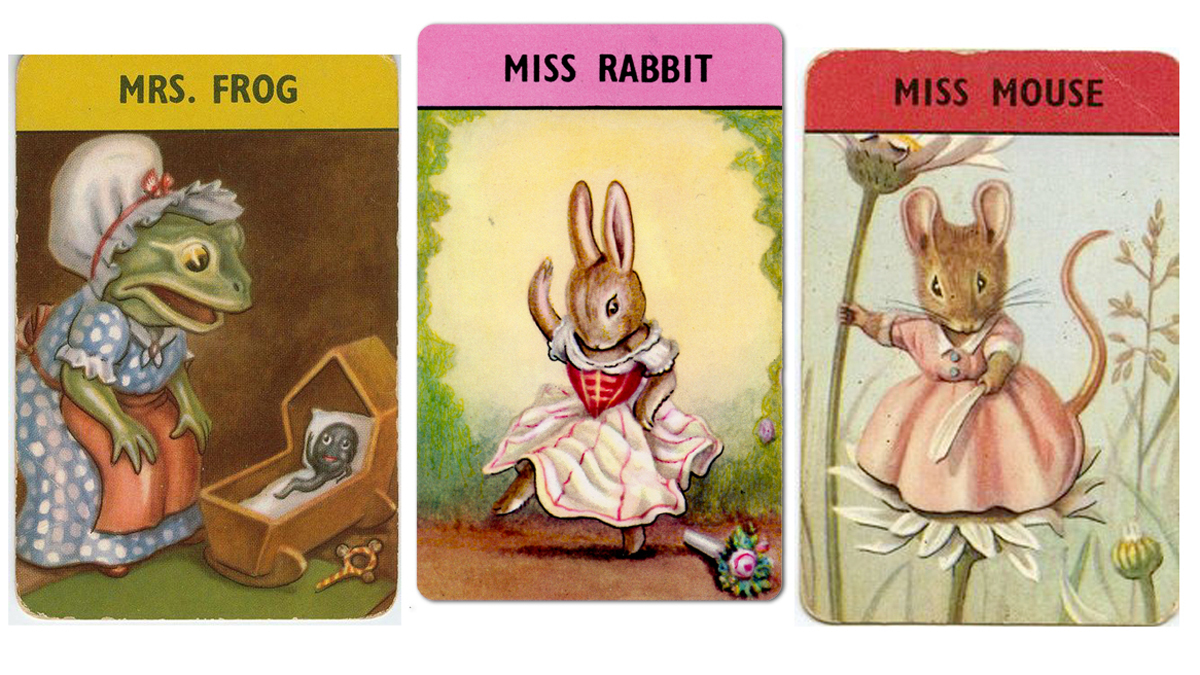

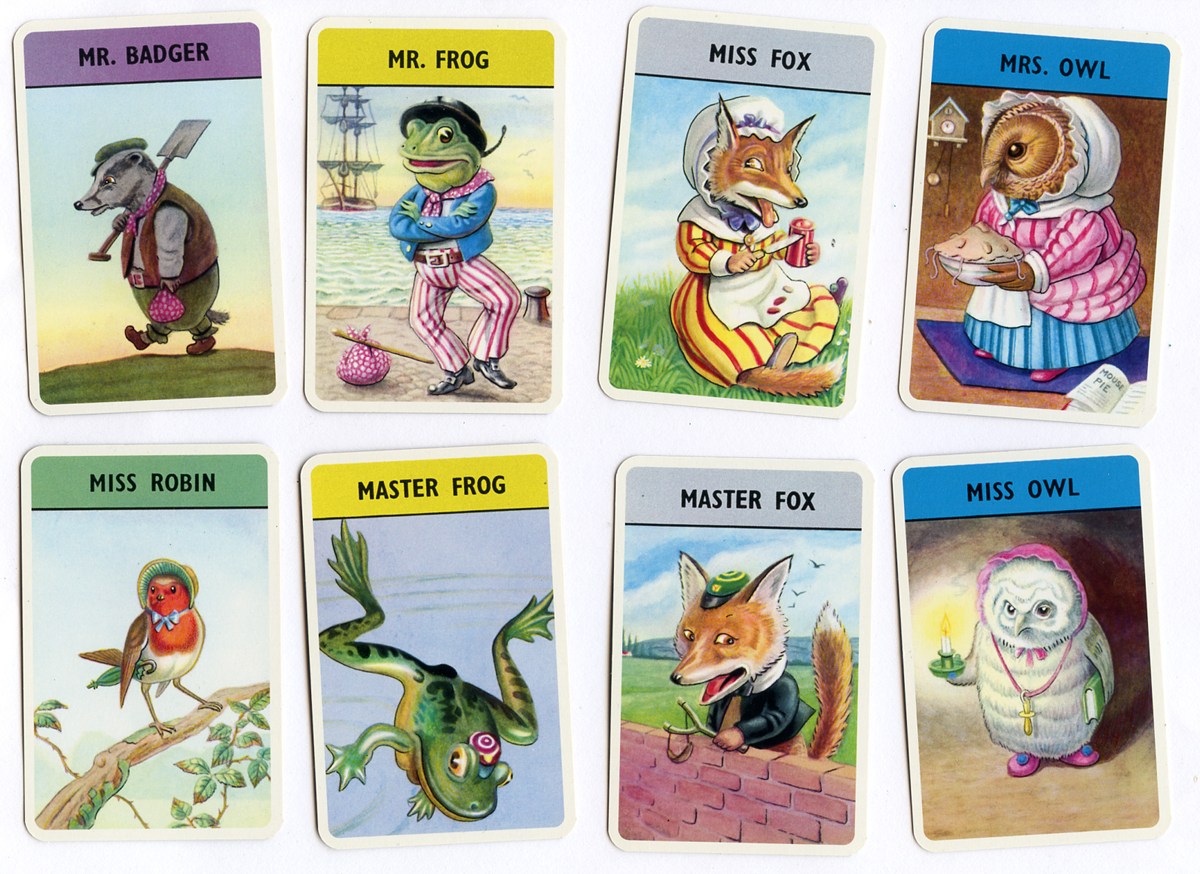

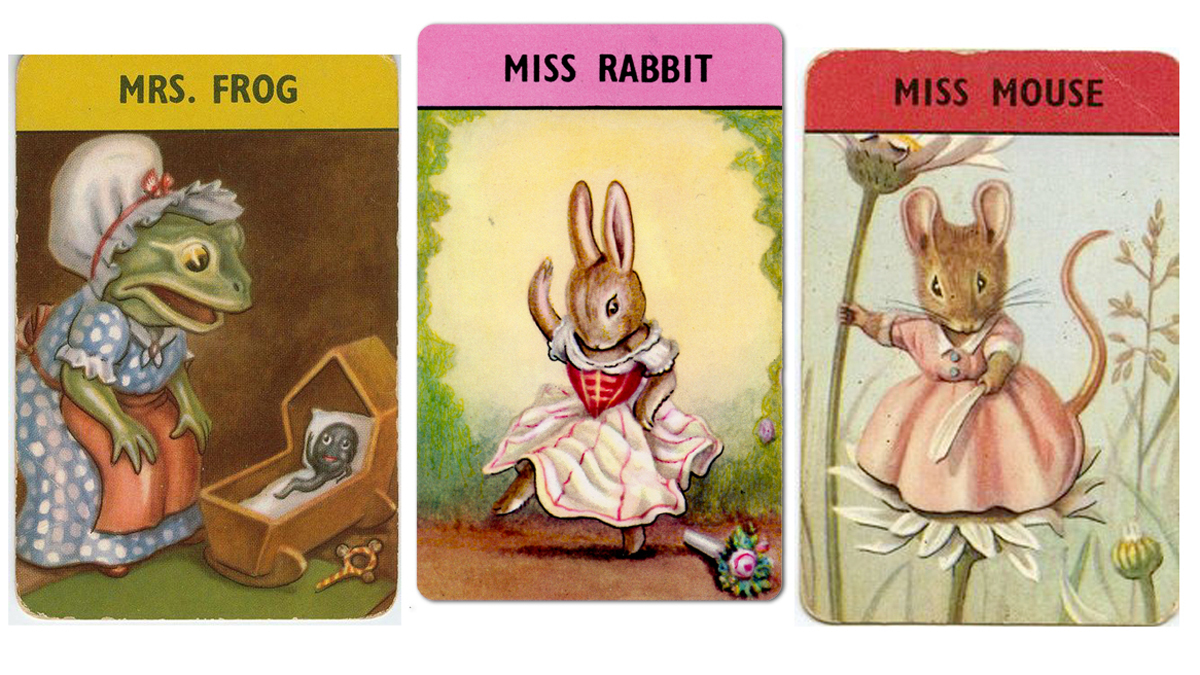

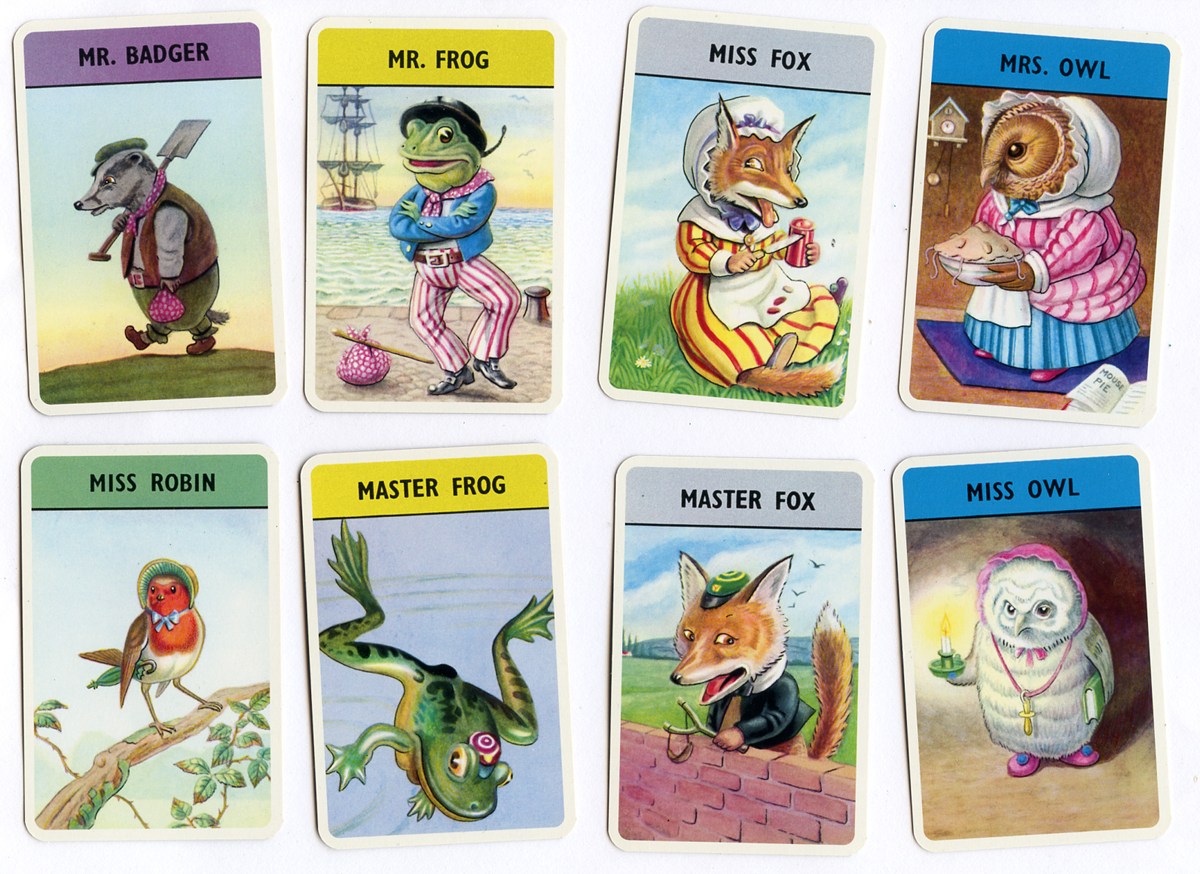

Some animals seem to need more dressing up than others. As a child I used to adore these animal illustrations for the Woodland Happy Families game by Racey Helps.

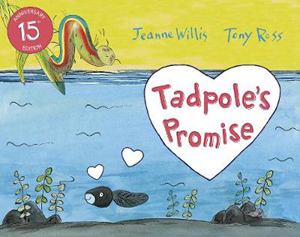

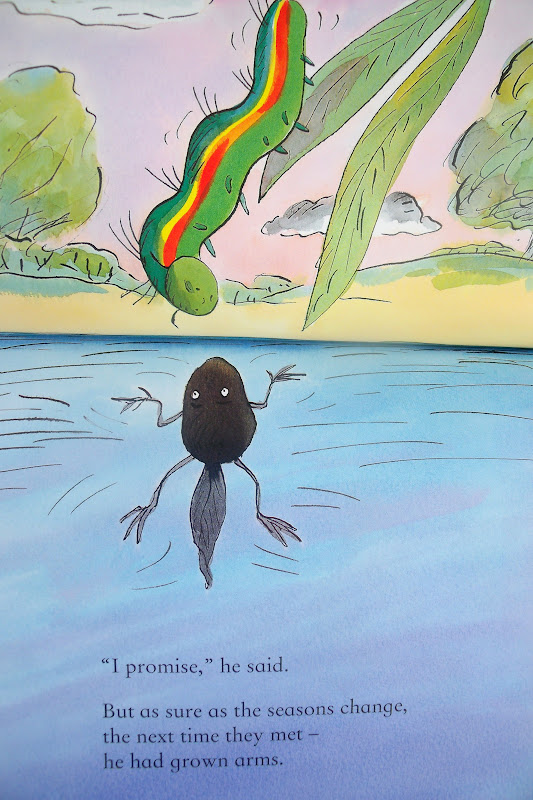

I love Mrs Frog’s expression as she gazes at her cheerily waving tadpole. My sister Jo and I used to play long and involved imaginary games with these cards as our avatars: – Jo was the glamorous Miss Rabbit and I was the slightly homelier Miss Mouse.

I do admire how Racey Helps’s animals are truly animal under their clothes – and have a look at Mrs Owl’s delicious pie. (Eeek. Don’t tell Miss Mouse.) The Woodland Happy Families are sometimes fully dressed complete with shoes, like Miss Fox, but other times just lightly accessorised, like Miss Robin. Master Frog is as nature intended as he goes for a swim, but Mr Frog has full sailor garb including little boots… (So how DO those flippers fit in? Better to skim quickly over questions like this when considering animal-dressing.)

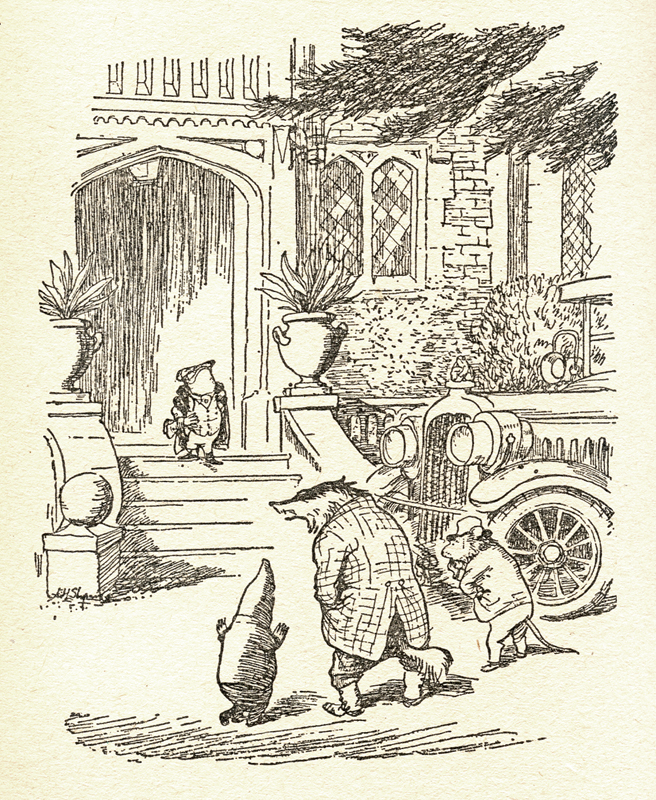

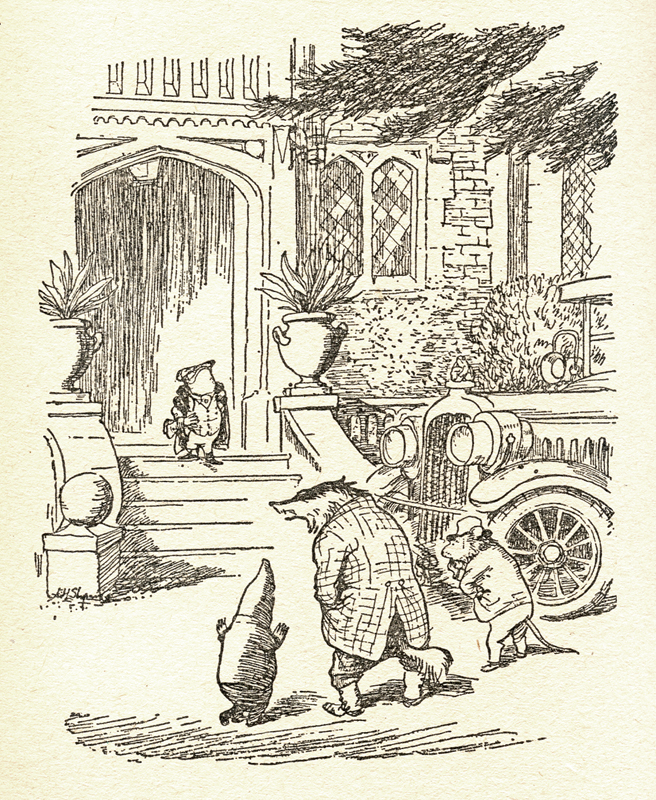

With EH Shepard the main characters are completely suited and booted. But the weasels and stoats just have the odd bag and hat – so it seems the less civilised & well-behaved you are, the less you wear. But then there’s practicality too: those swimmers Otter and his son Portly don’t wear clothes either.

Inga Moore

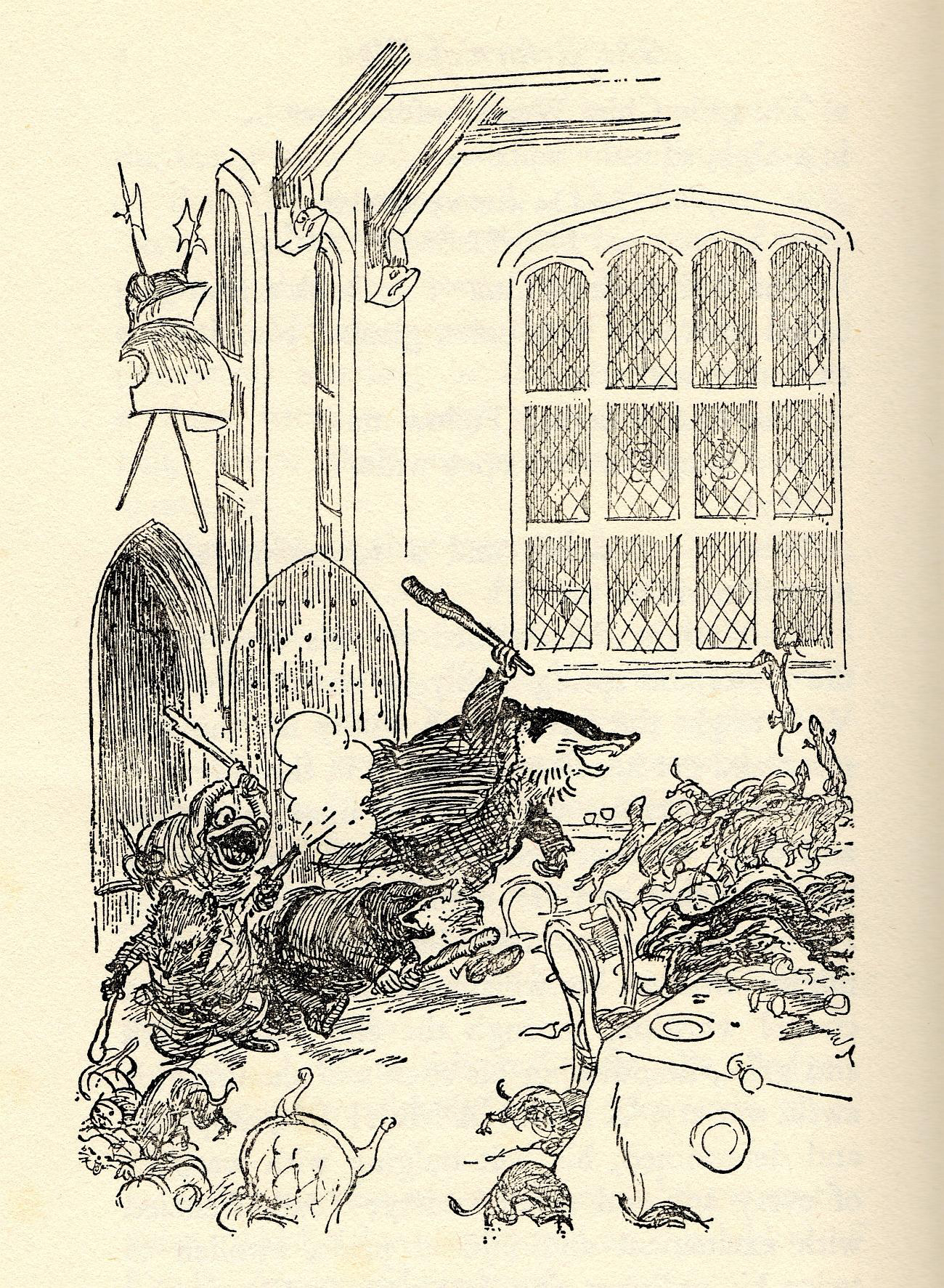

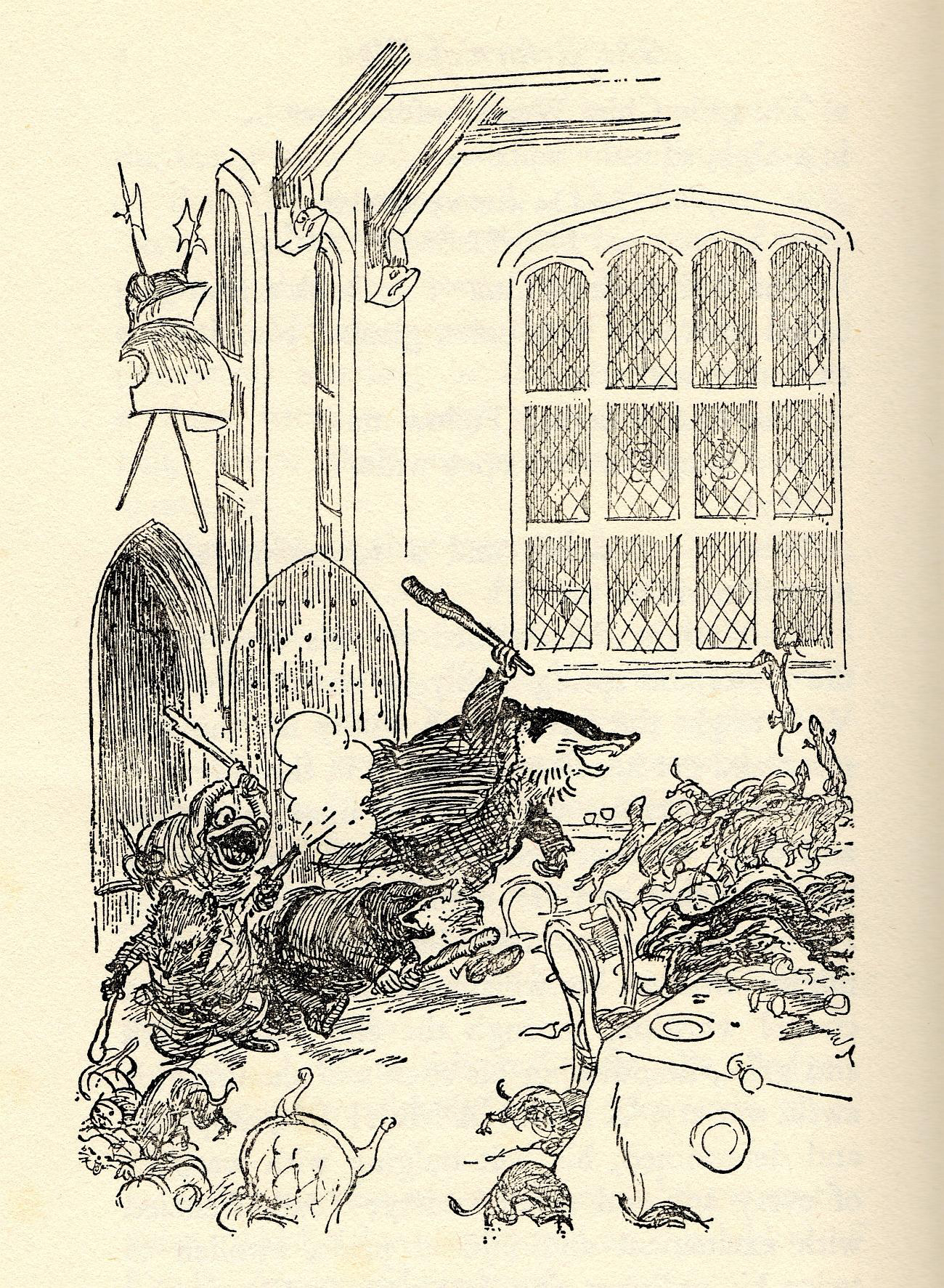

Here’s the battle of Toad Hall: Badger, Mole, Toad and Ratty are all showing their claws and teeth like proper animals on the warpath. The tiny weasels seem to have abandoned any pretence at civilisation and become pure animal as they scuttle away in terror. There is a bit of animal stereotyping in Wind in the Willows: weasels are actually brave, fierce and bonkers little animals – but in Wind in the Willows, as Ratty says: “well, you can’t really trust them, and that’s the fact.” It could be that the uprising of the less-well-dressed animal underclasses foreshadows the social upheaval of the First World War, and the unwinding of the Edwardian age of servants and huge hampers.

Here’s the battle of Toad Hall: Badger, Mole, Toad and Ratty are all showing their claws and teeth like proper animals on the warpath. The tiny weasels seem to have abandoned any pretence at civilisation and become pure animal as they scuttle away in terror. There is a bit of animal stereotyping in Wind in the Willows: weasels are actually brave, fierce and bonkers little animals – but in Wind in the Willows, as Ratty says: “well, you can’t really trust them, and that’s the fact.” It could be that the uprising of the less-well-dressed animal underclasses foreshadows the social upheaval of the First World War, and the unwinding of the Edwardian age of servants and huge hampers.

Here’s the same scene pictured by Inga Moore. Again, the weasels are just minimally accessoried and you can imagine the blood-curdling war-growls coming from Badger.

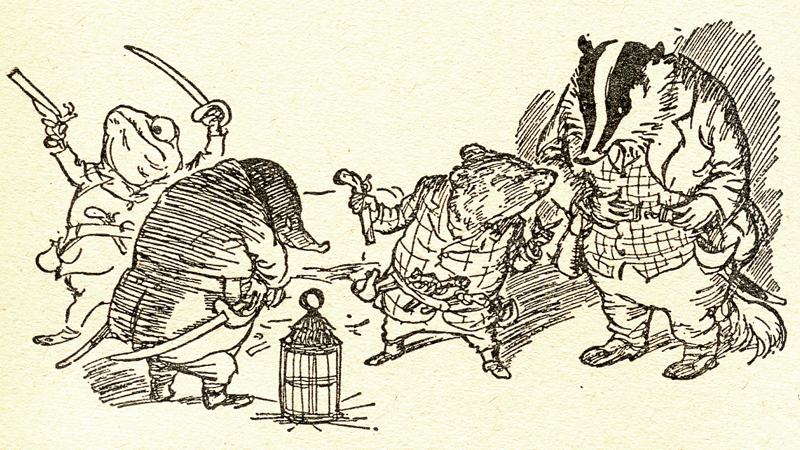

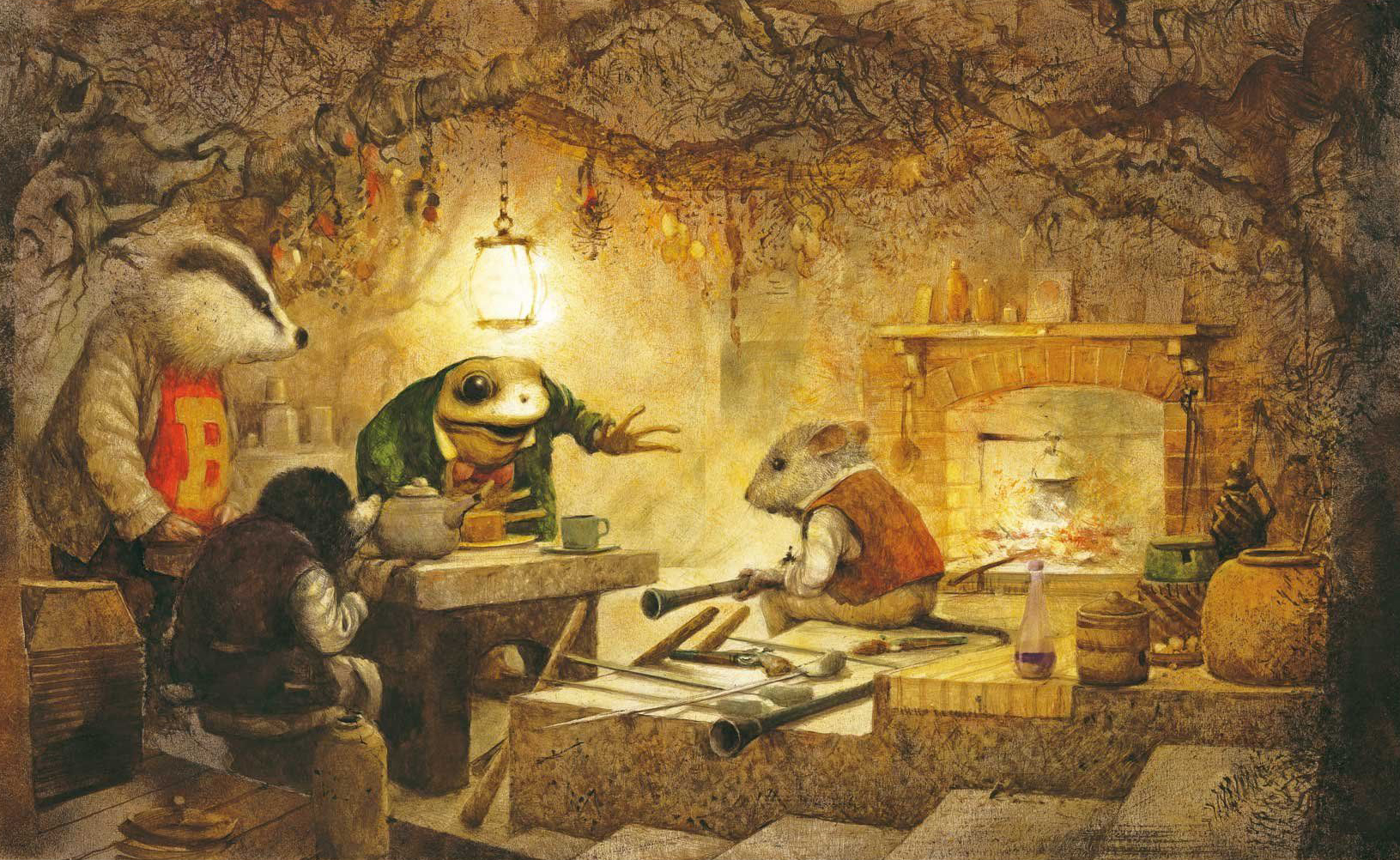

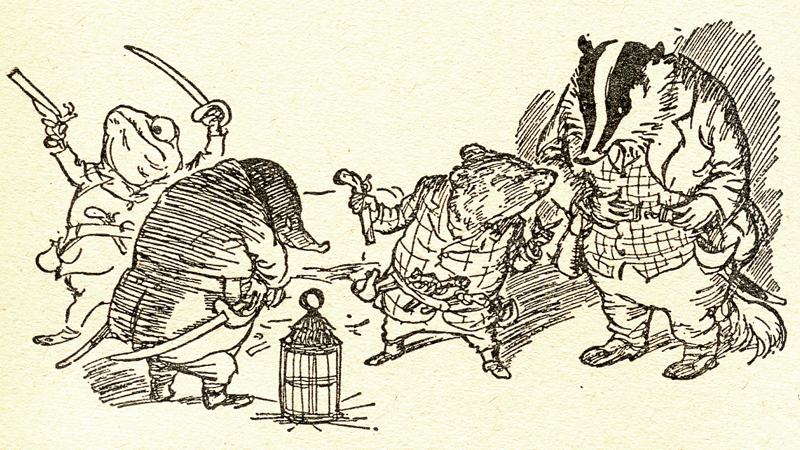

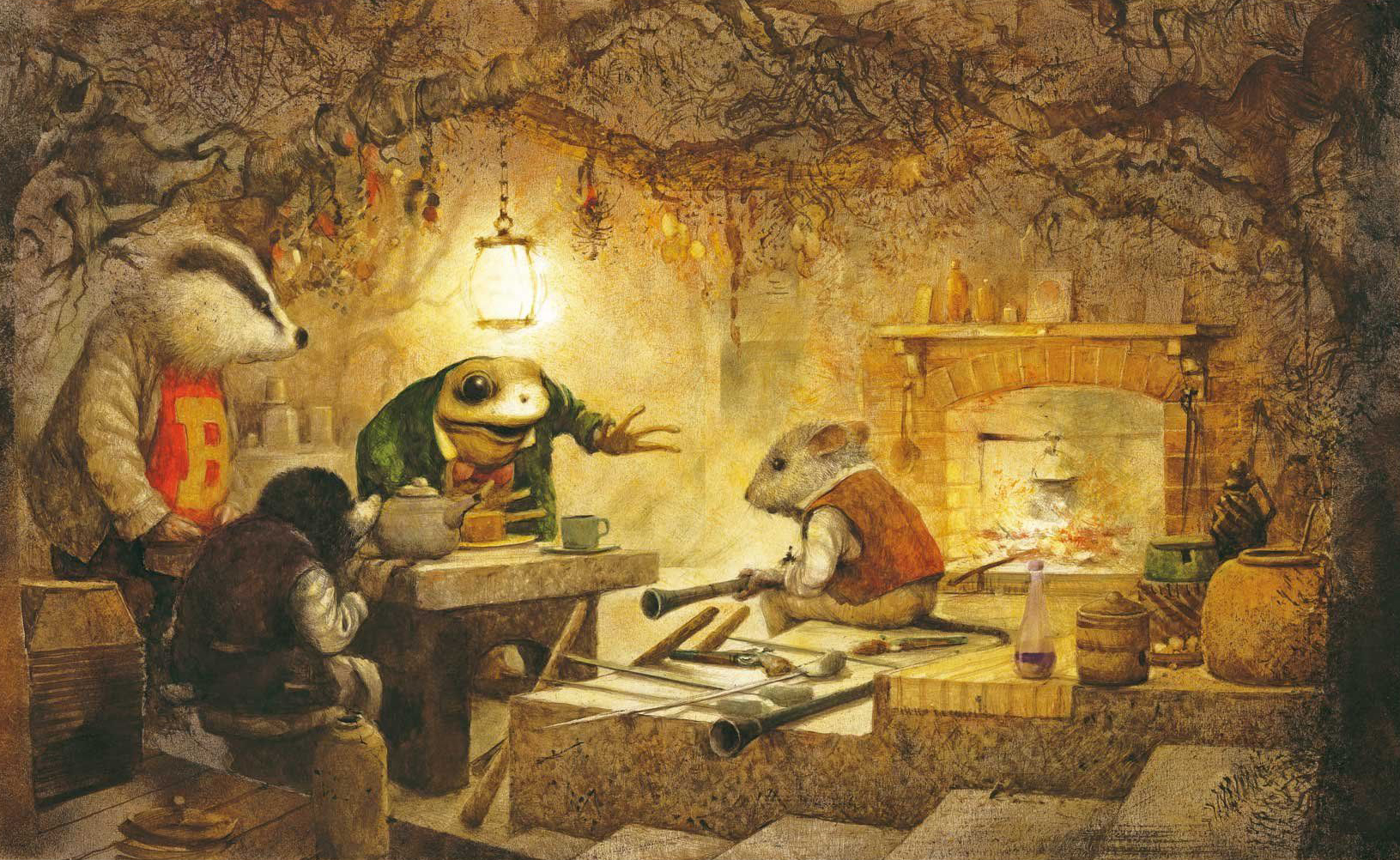

Here they are getting weaponed up for the battle.

I love Mole’s hunched and determined posture.

Inga Moore

Here’s Shepard’s Mole again doing a leap, with its stumpy rounded shape, true to animal form.

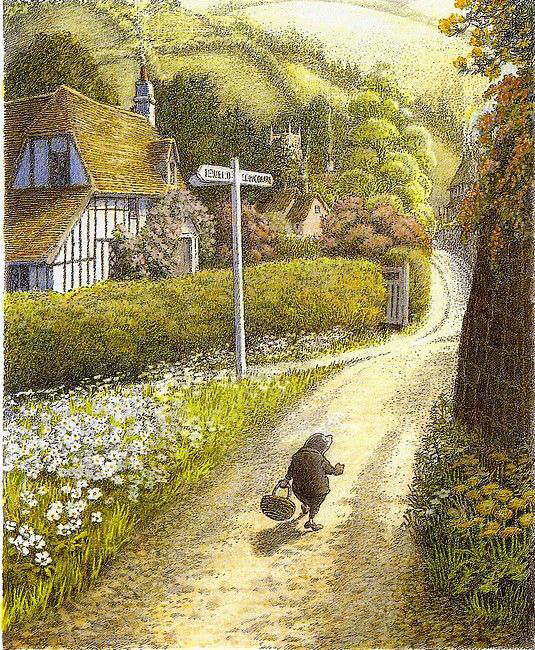

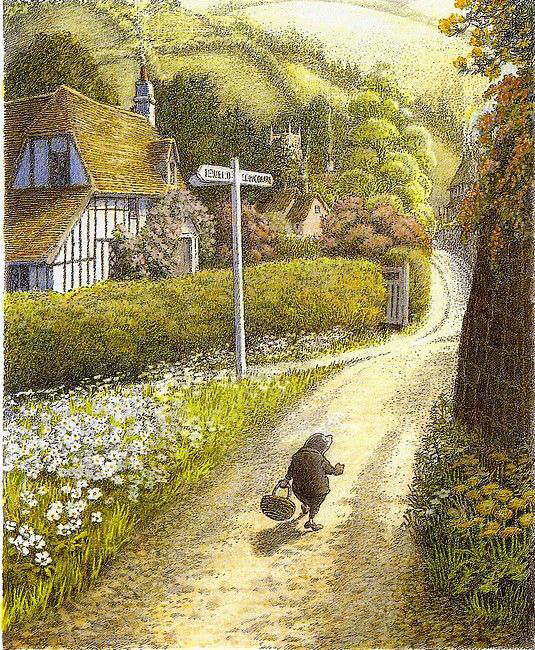

Here is Inga Moore’s Mole strolling through a glorious landscape.

Arthur Rackham

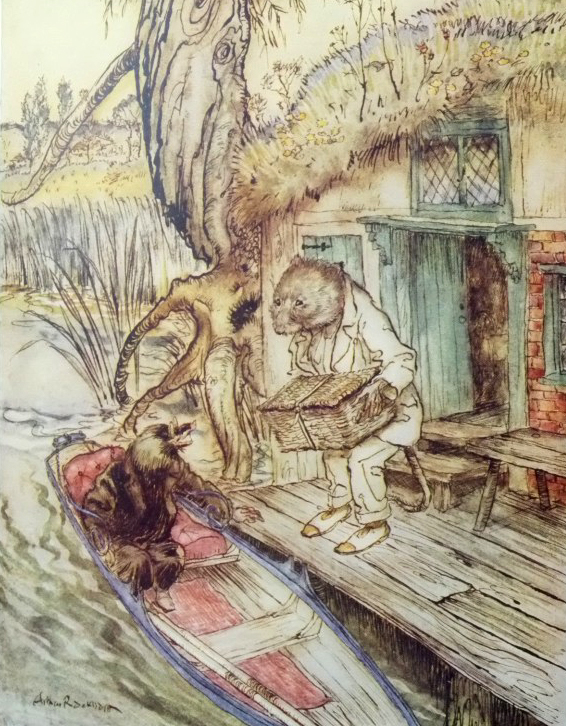

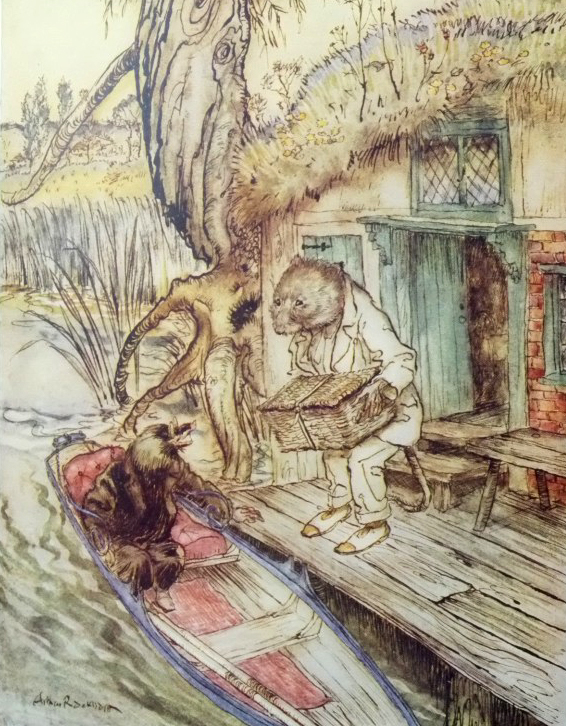

The Wind in the Willows was the last book Arthur Rackham illustrated.

EH Shepard

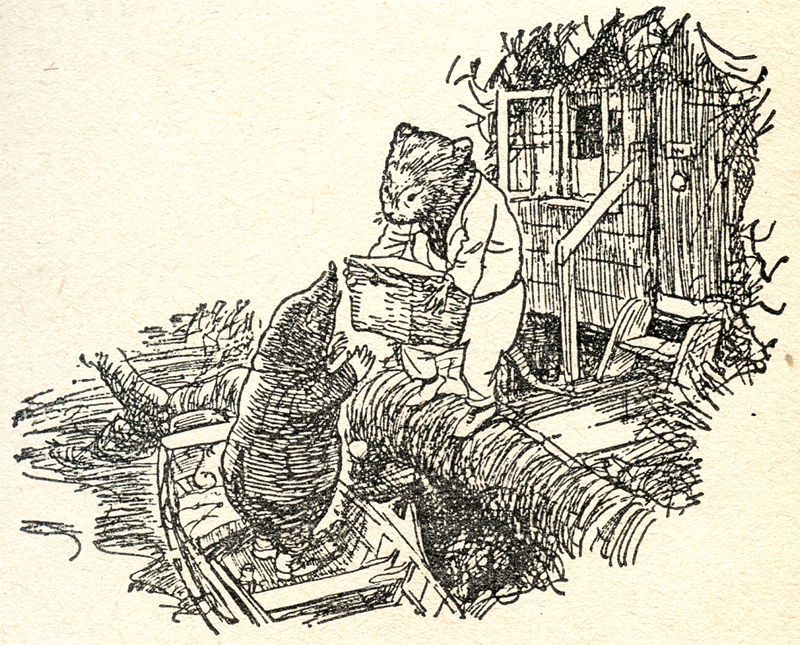

Here’s his Ratty loading up the boat with that all-important luncheon basket. To me Rackham’s animals seem more human in form than Shepard’s, with longer limbs and more human knees and elbows.

Here’s the same scene from EH Shepard.

Robert Ingpen

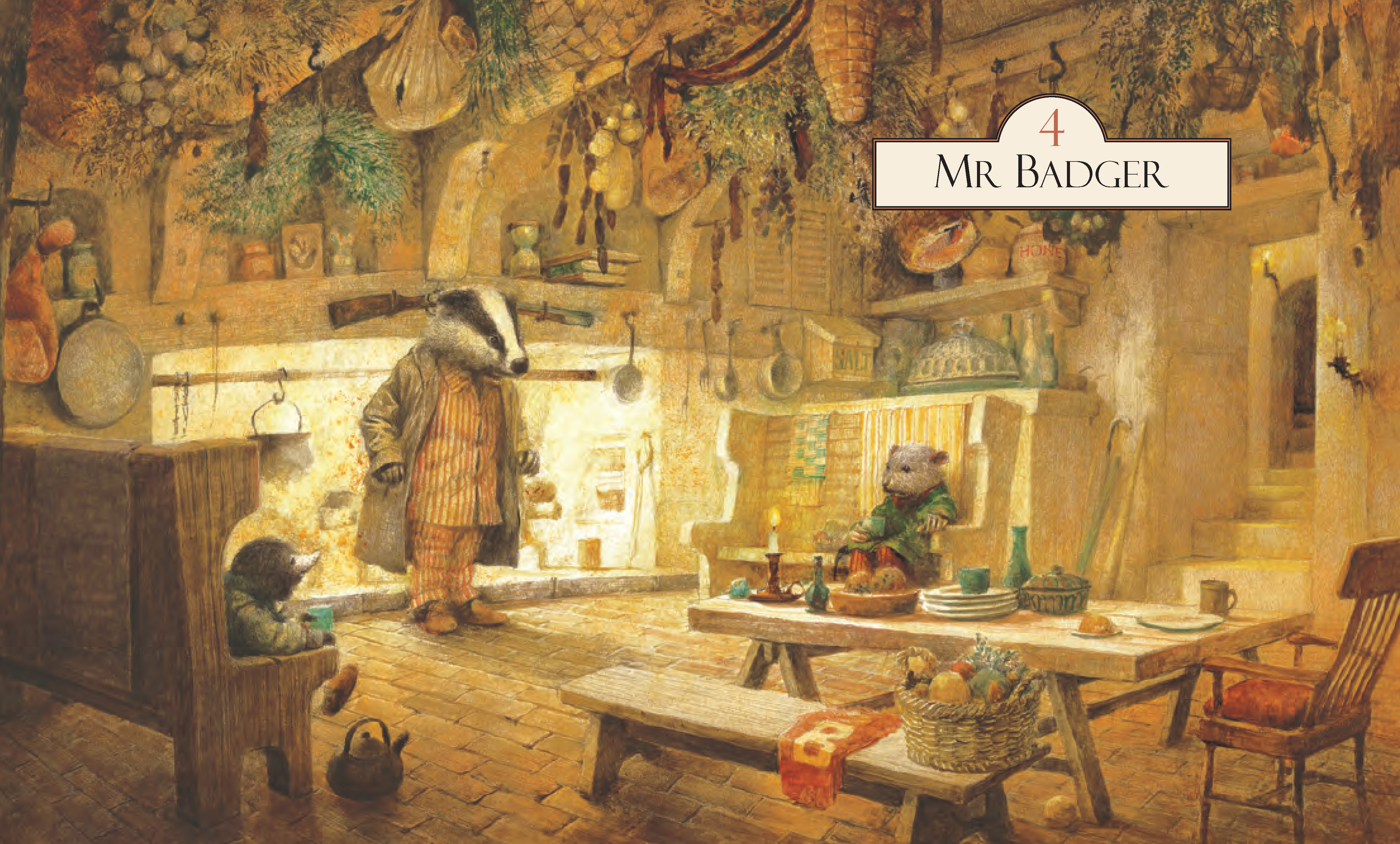

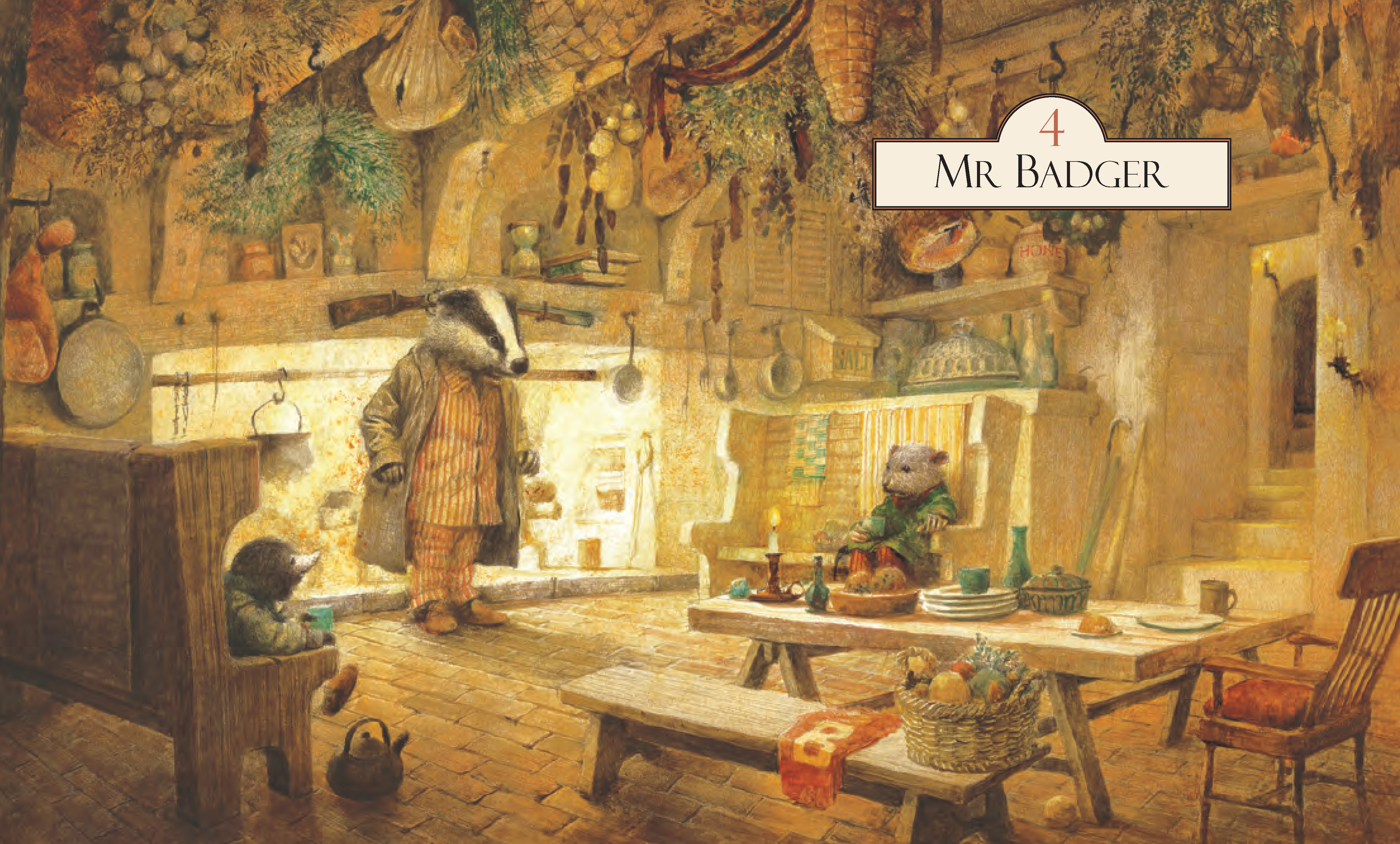

Some glowingly depicted scenes by Robert Ingpen.

Robert Ingpen

But let’s return to the luncheon basket.

EH Shepard

The Luncheon Basket

Arthur Rackham

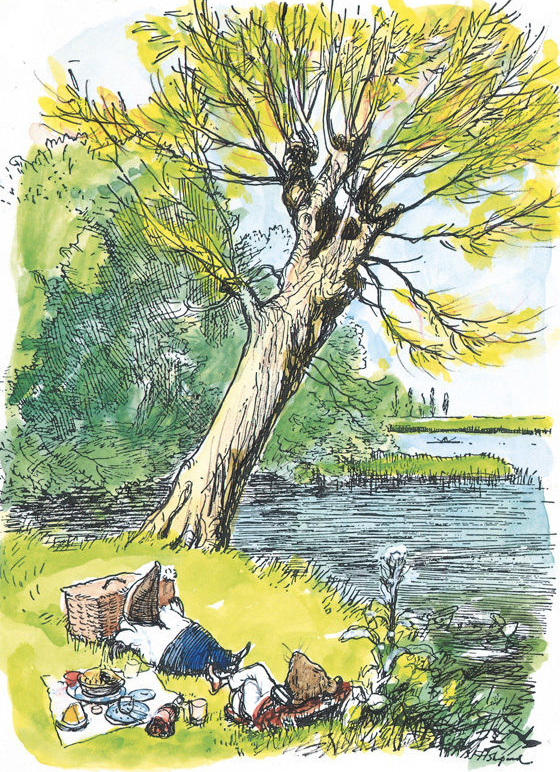

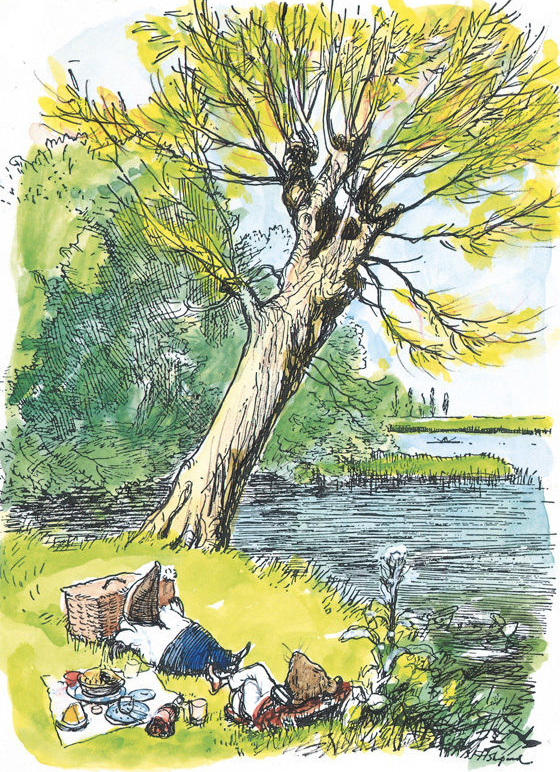

Here are Shepard’s Ratty and Mole stretching out after their picnic.

And here are Rackham’s animals laying out their spread.

That luncheon basket!

“What’s inside it?” says Mole…

David Roberts

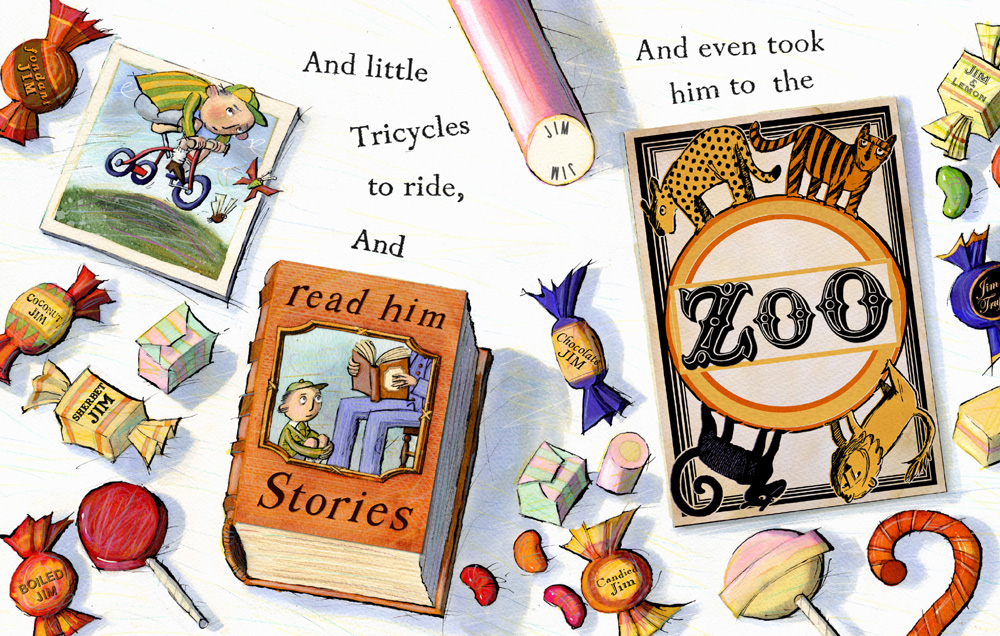

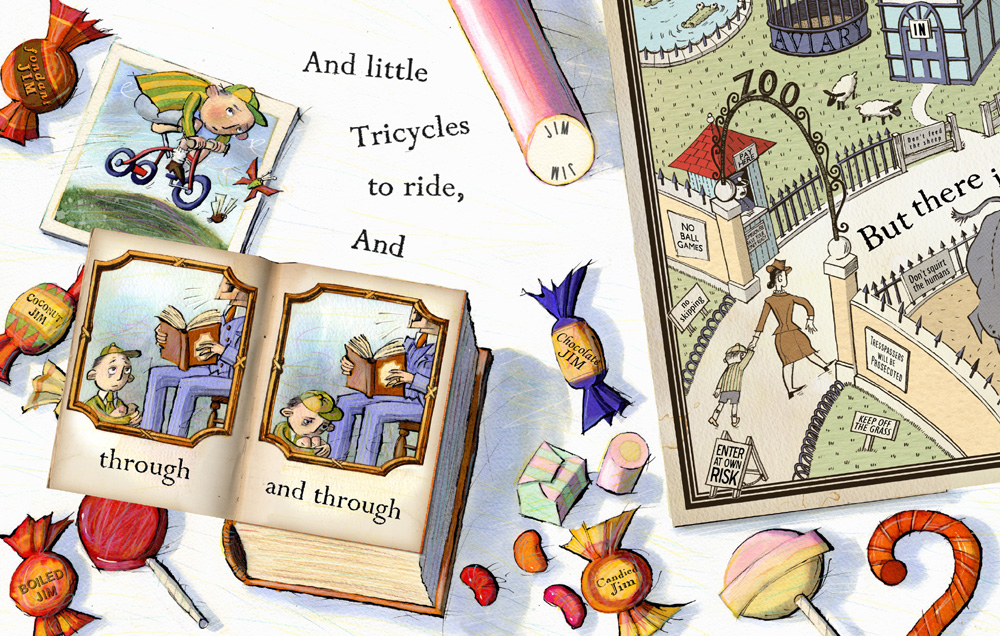

And that’s a slight problem to me, as I know that moles eat mainly worms, grubs and insects, and water voles like Ratty eat vegetation mostly. And I do believe in being true to zoology. But as an illustrator I don’t think you can avoid drawing the beautiful meat-heavy pies described in that Edwardian picnic. It just wouldn’t be doing the picnic justice if you did.

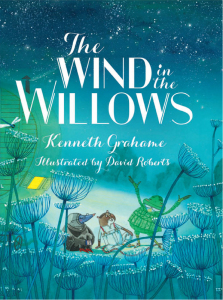

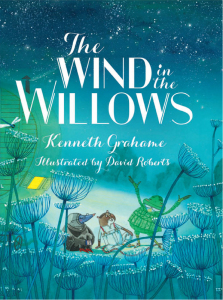

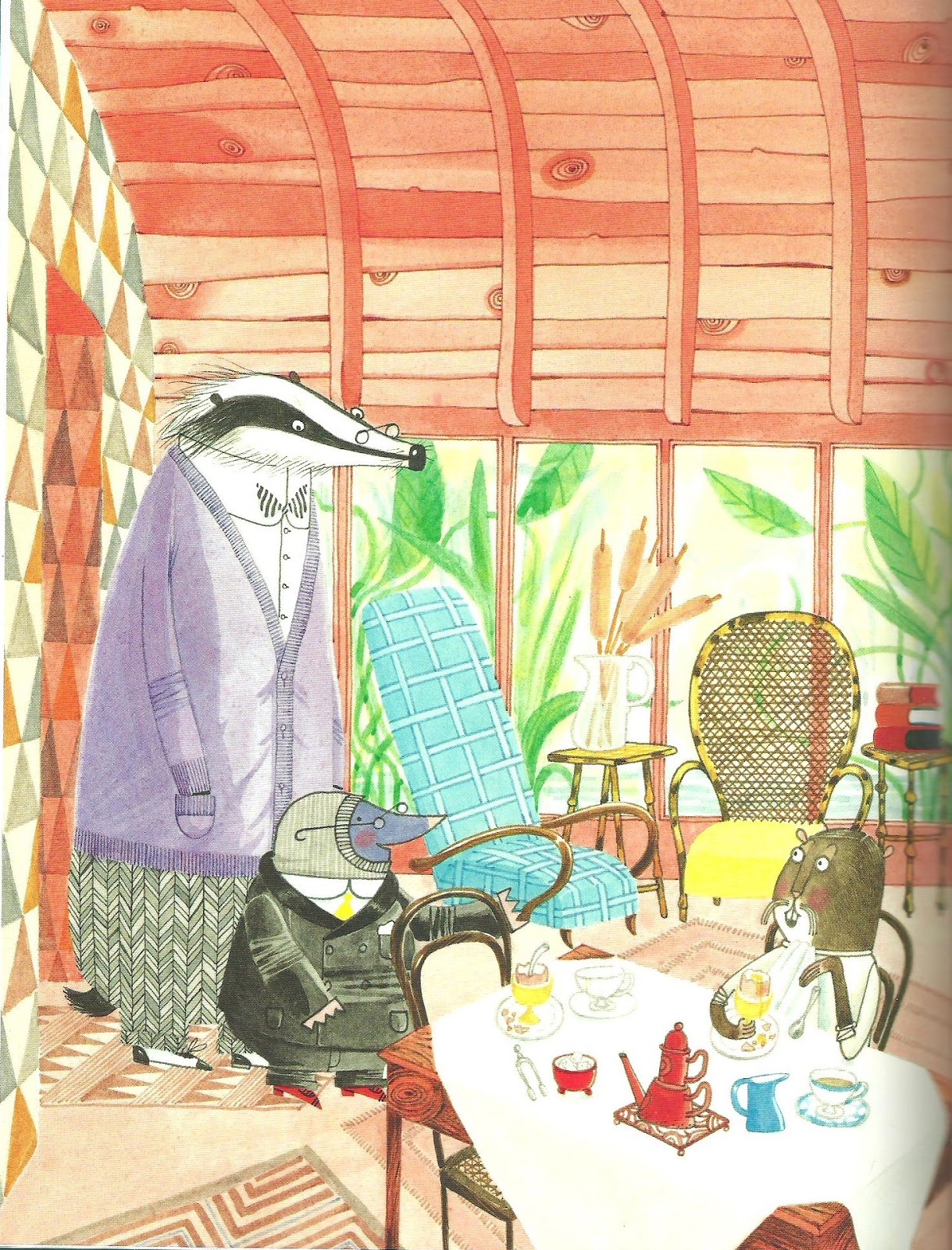

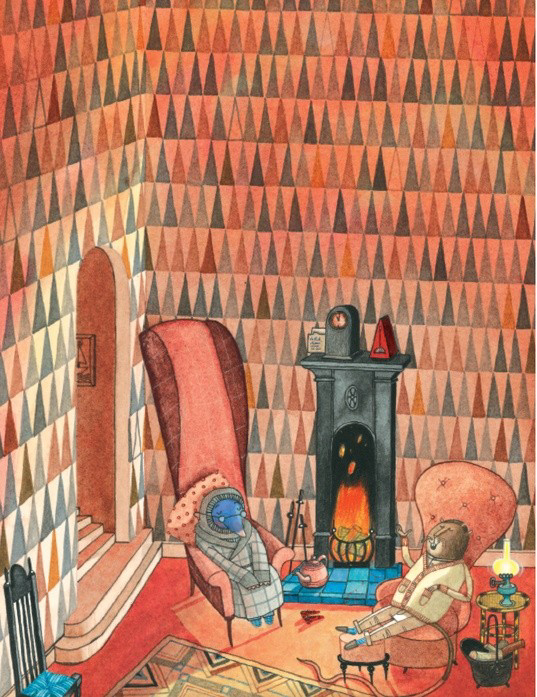

But the copy of Wind in the Willows I treasure is this version by David Roberts.

David Roberts

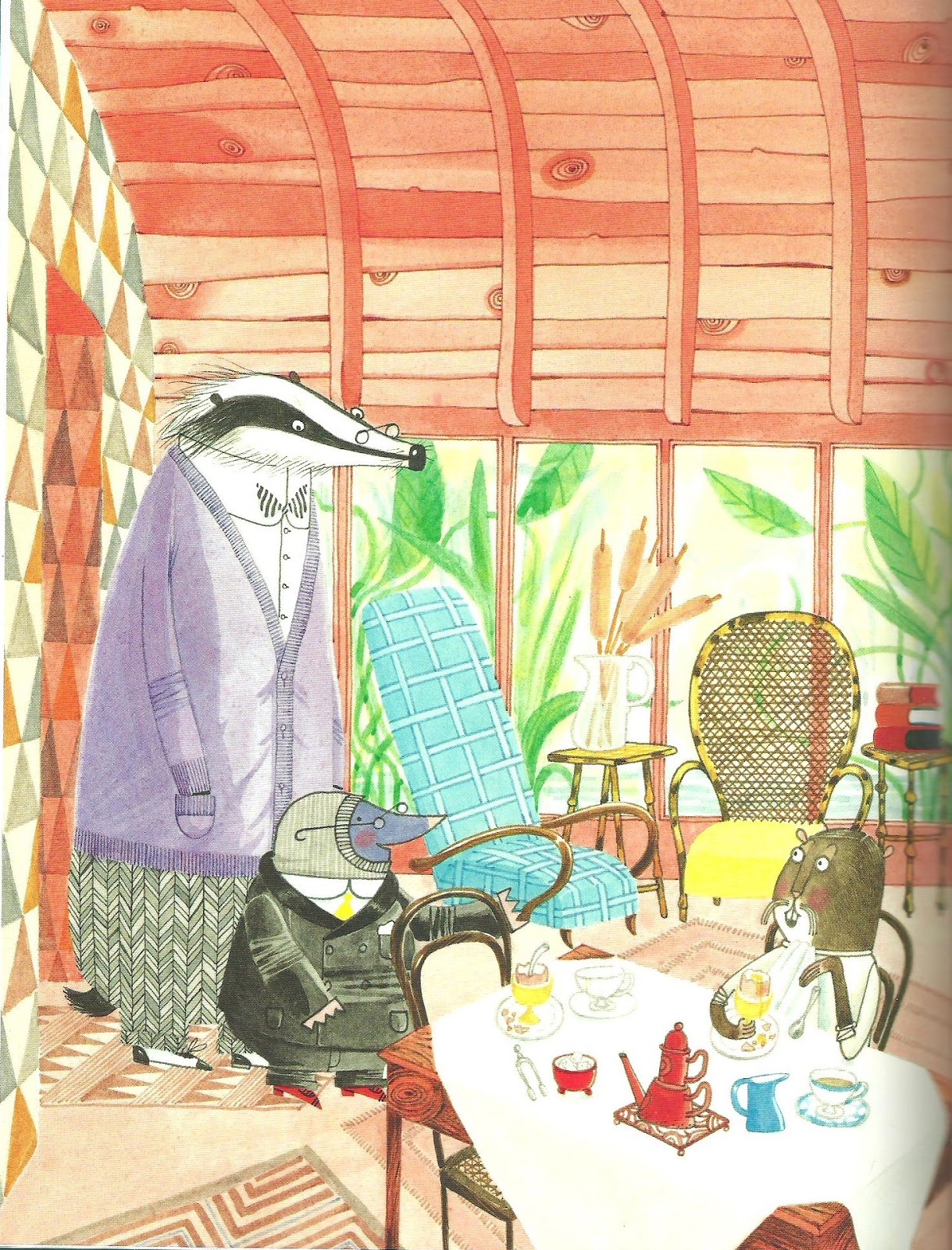

I love the carefully designed outfits: Mole’s velvety moleskin suit, badger’s tweeds and cardigan, Ratty’s Edwardian sporting whites.

David Roberts

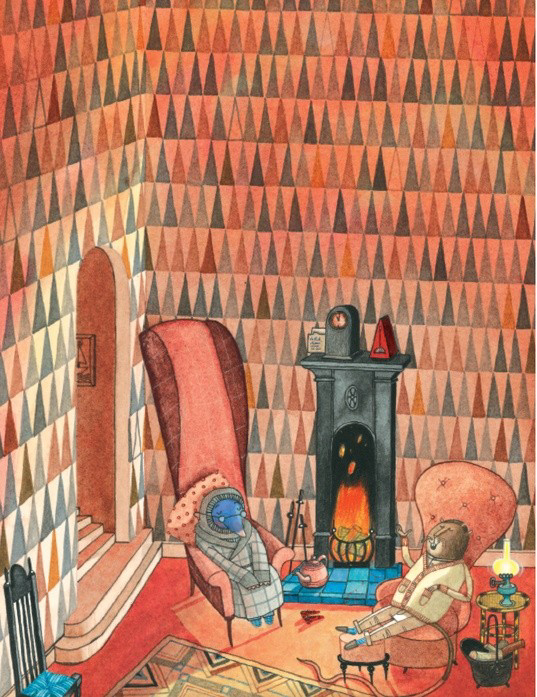

The beautiful elegant Edwardian furniture, the audacious interiors…

David Roberts

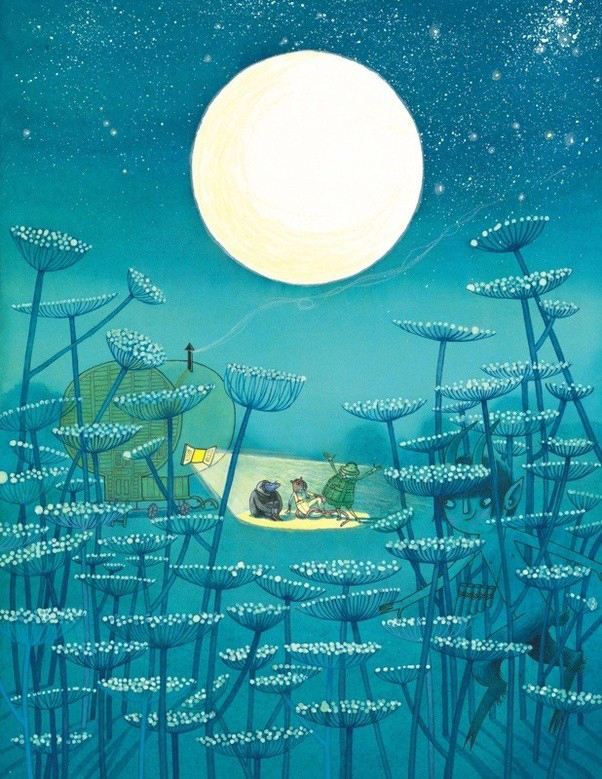

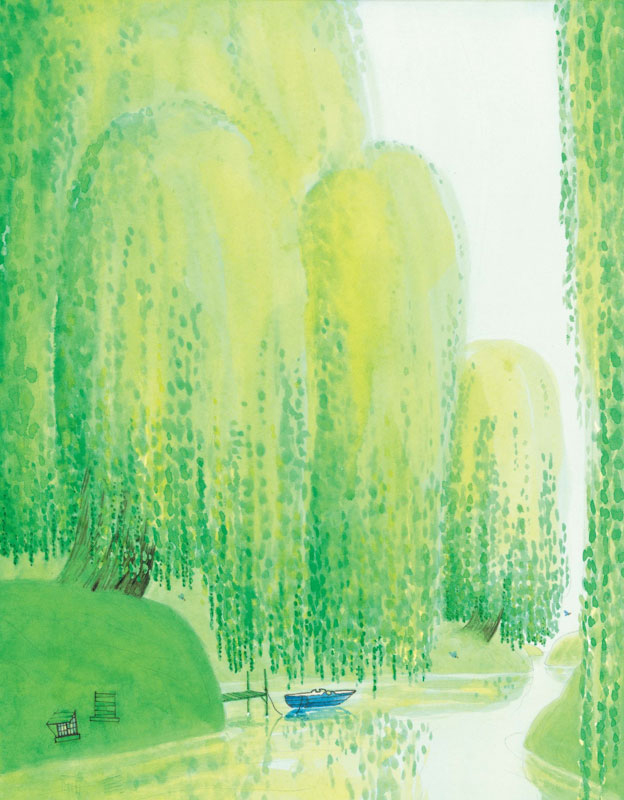

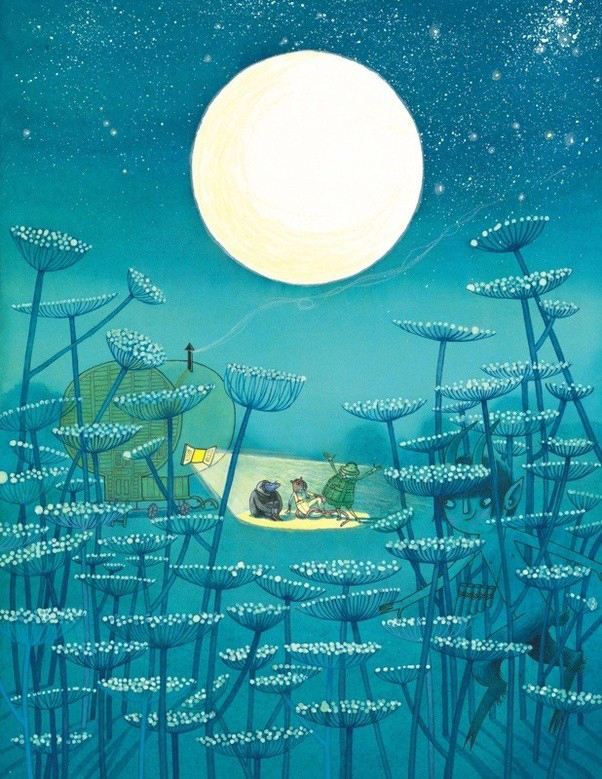

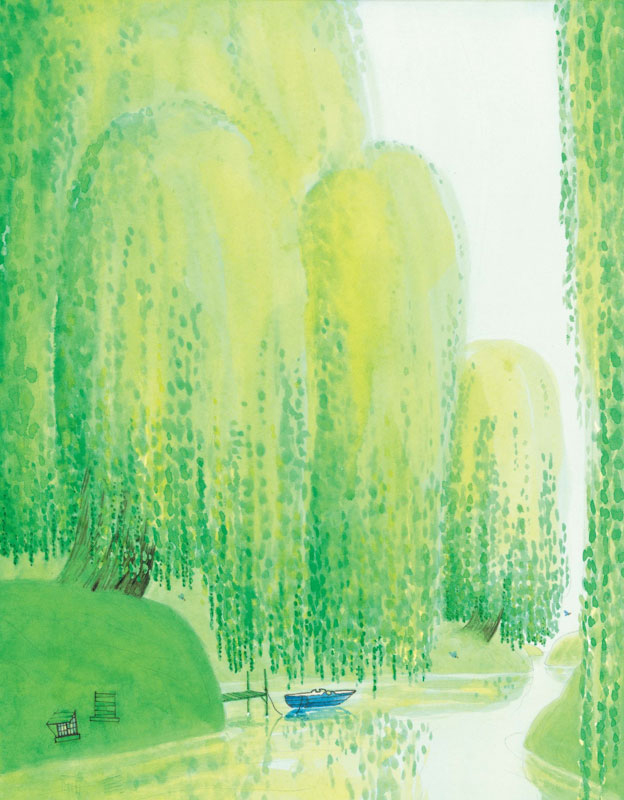

and the pure poetry, the light and space:

a moonlit field of cow parsley (with a hidden Pan),

mole submerged in bubbles and green water,

David Roberts

and this vista of willow weeping over.

But now let’s return to the very naughty Mr Toad.

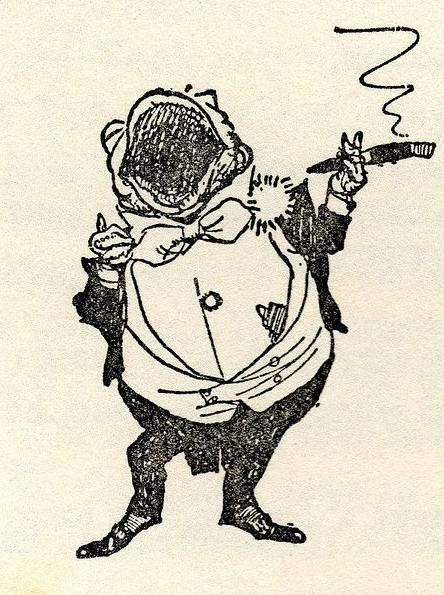

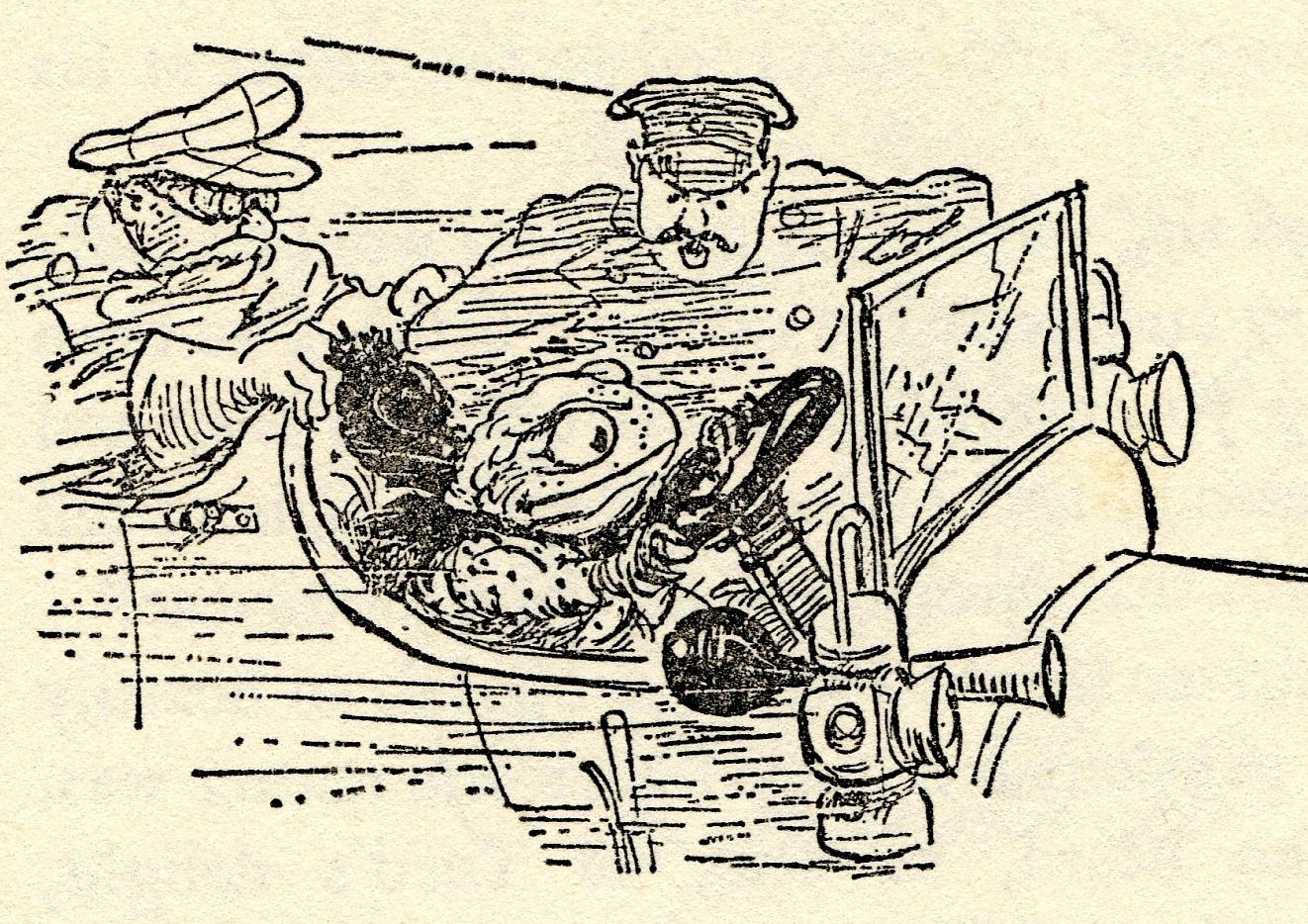

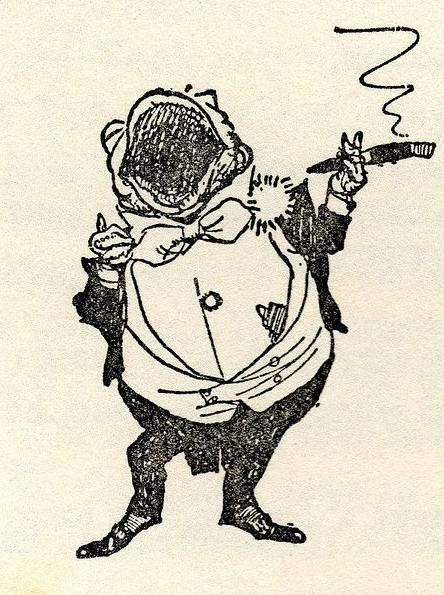

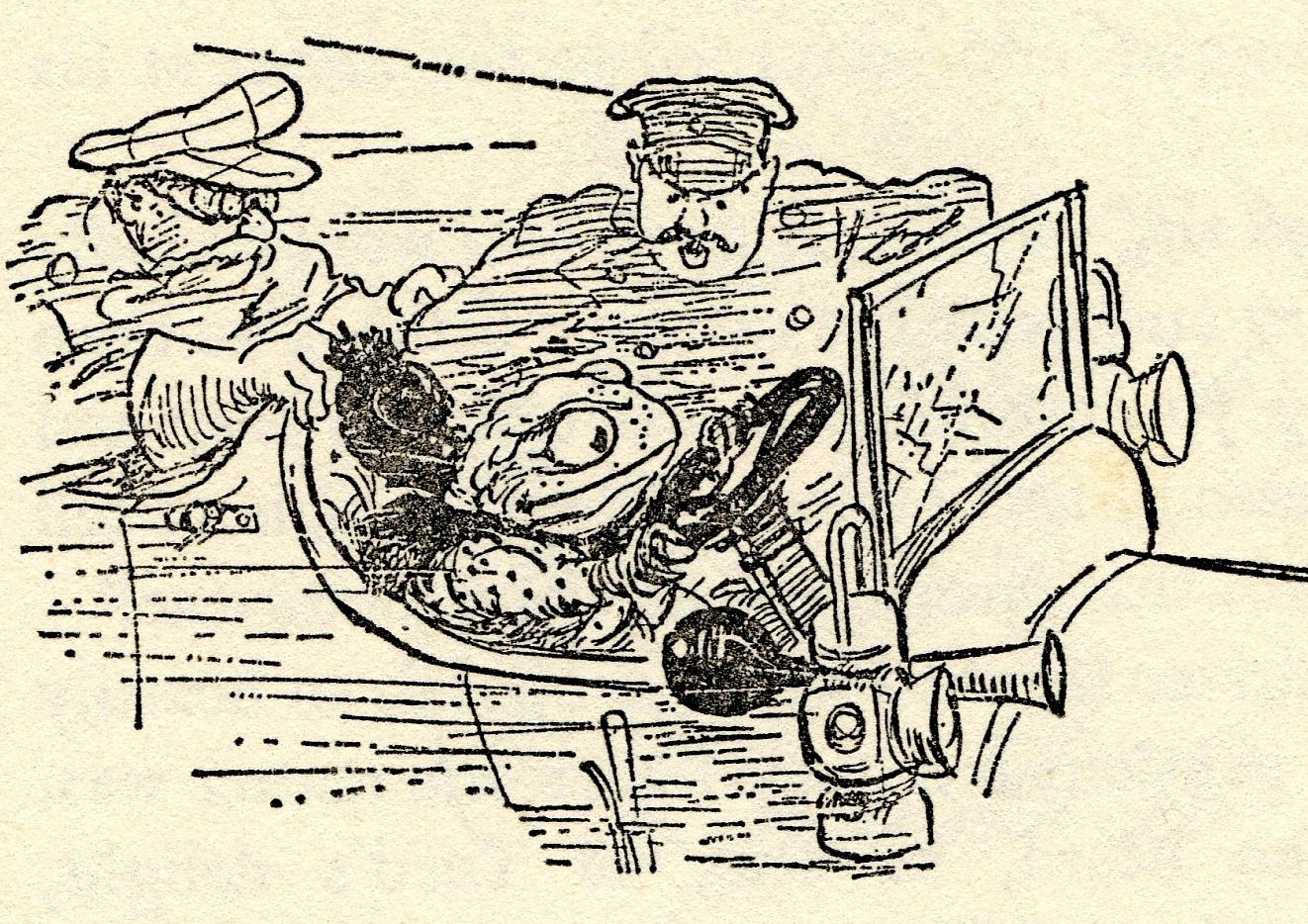

My favourite depiction of Toad has to be EH Shepard’s: irrepressible, unrepentant– a high-speed amphibian obsessed with the automobile.

He is unsquashable, impetuous, possessed by an almost consumerist passion for the Motor Car.

The Car!

1907 saw the advent of the luxurious Rolls Royce Silver Ghost – “Silent as a Ghost, Powerful as a Lion, and Trustworthy as Time” – aristocratic motoring indeed.

But in 1908 Henry Ford brought out the Model T Ford, bringing motoring to everybody – the coming of the car – and for the last 111 years our cars have been the blind influence in charge of shaping our landscapes.

Toad is enraptured and enthralled by the Car – “The only way to travel – here today, in next week tomorrow!”

So the Willows shows this brand new force for a changing pace of life. And it’s torn between the urge to roam in dangerous places versus being safely cuddled up at home with toasted teacakes.

The Unbuilt Roads of Oxford Past

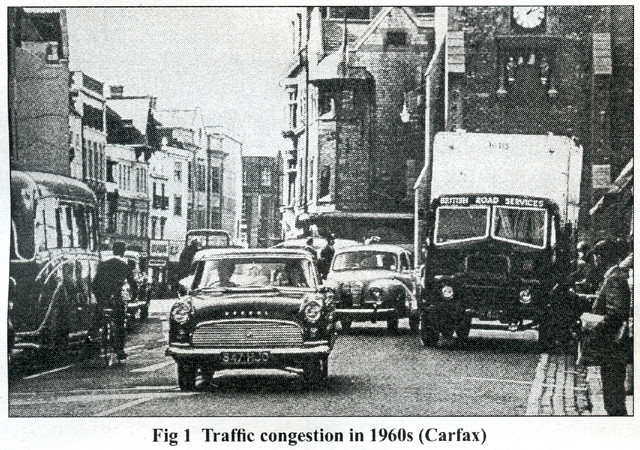

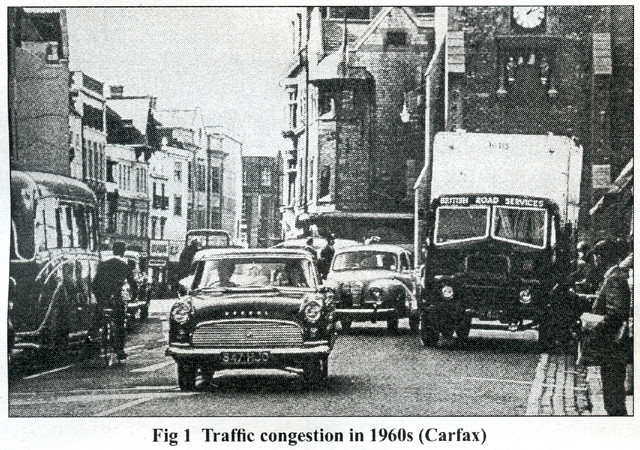

In the 1900s was the dawning of the Age of the Car, and by the 1960s the needs of car-travel was taking a major role in shaping city planning.

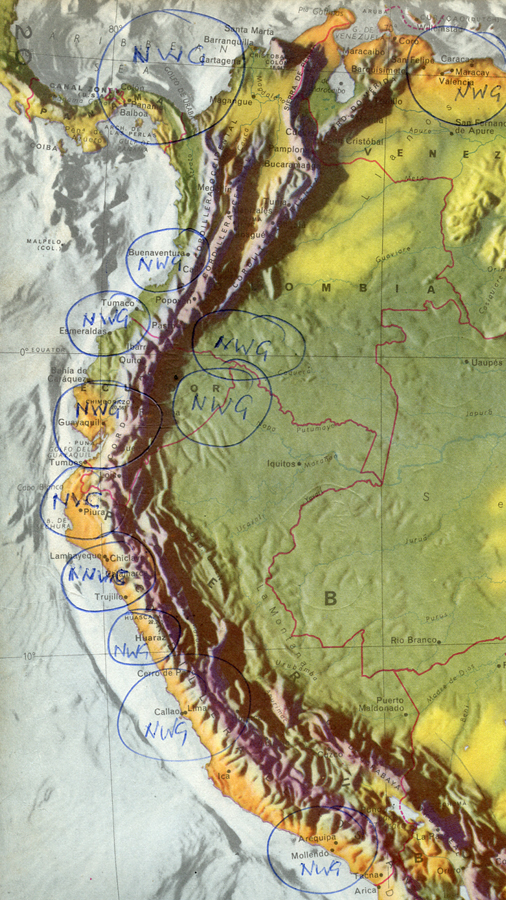

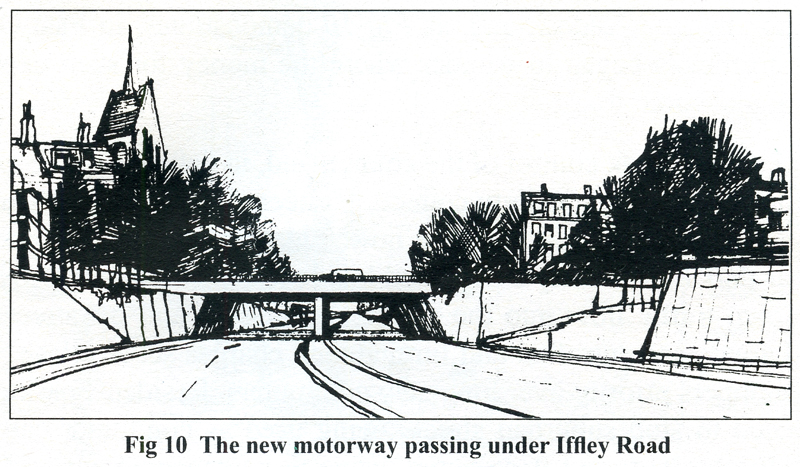

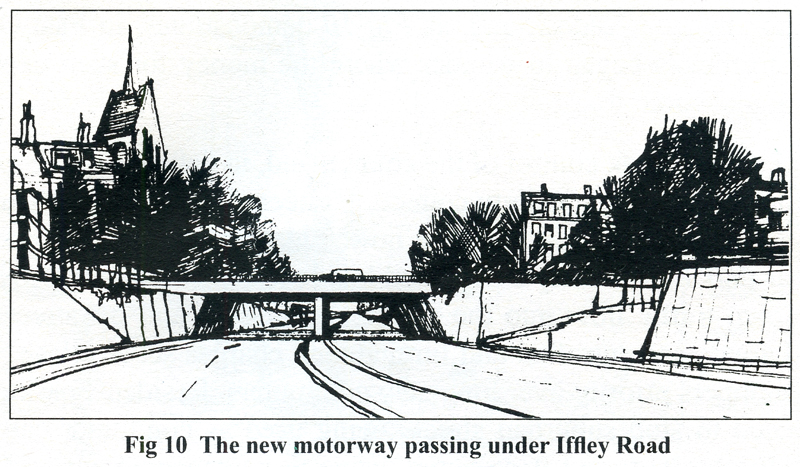

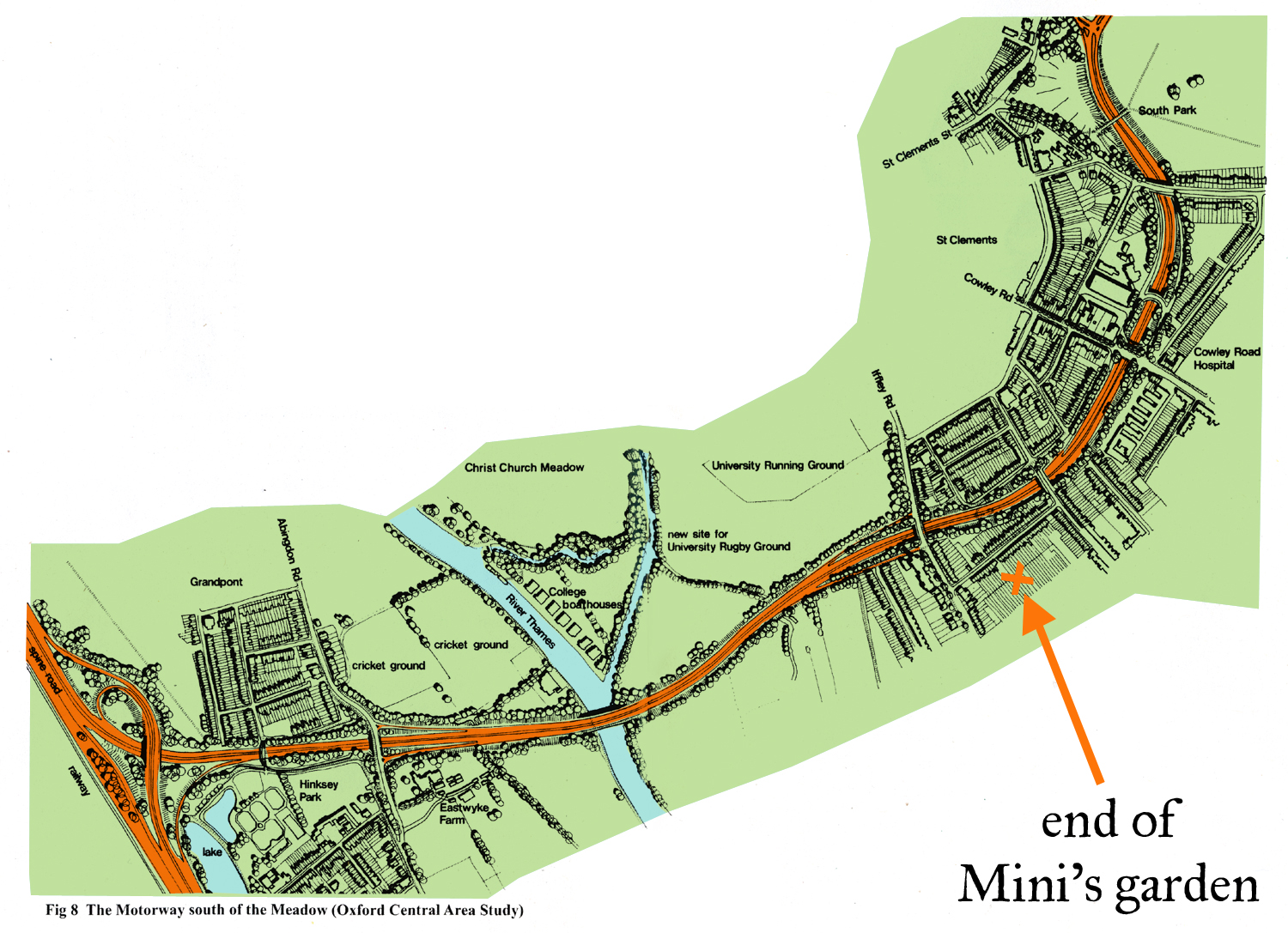

And in 1969 Oxford nearly had a superhighway built right through it. The city was very congested, traffic went right through the centre of it, so plans started to be hatched to make an inner relief road to speed up car travel times. Various schemes were planned, culminating in a planned motorway along the railway line and 4 lane west-east highway right through East Oxford.

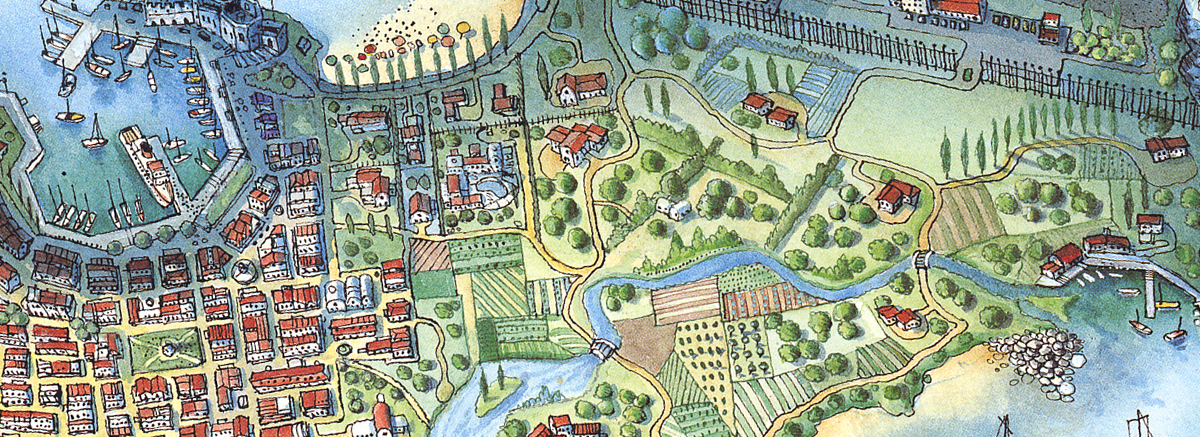

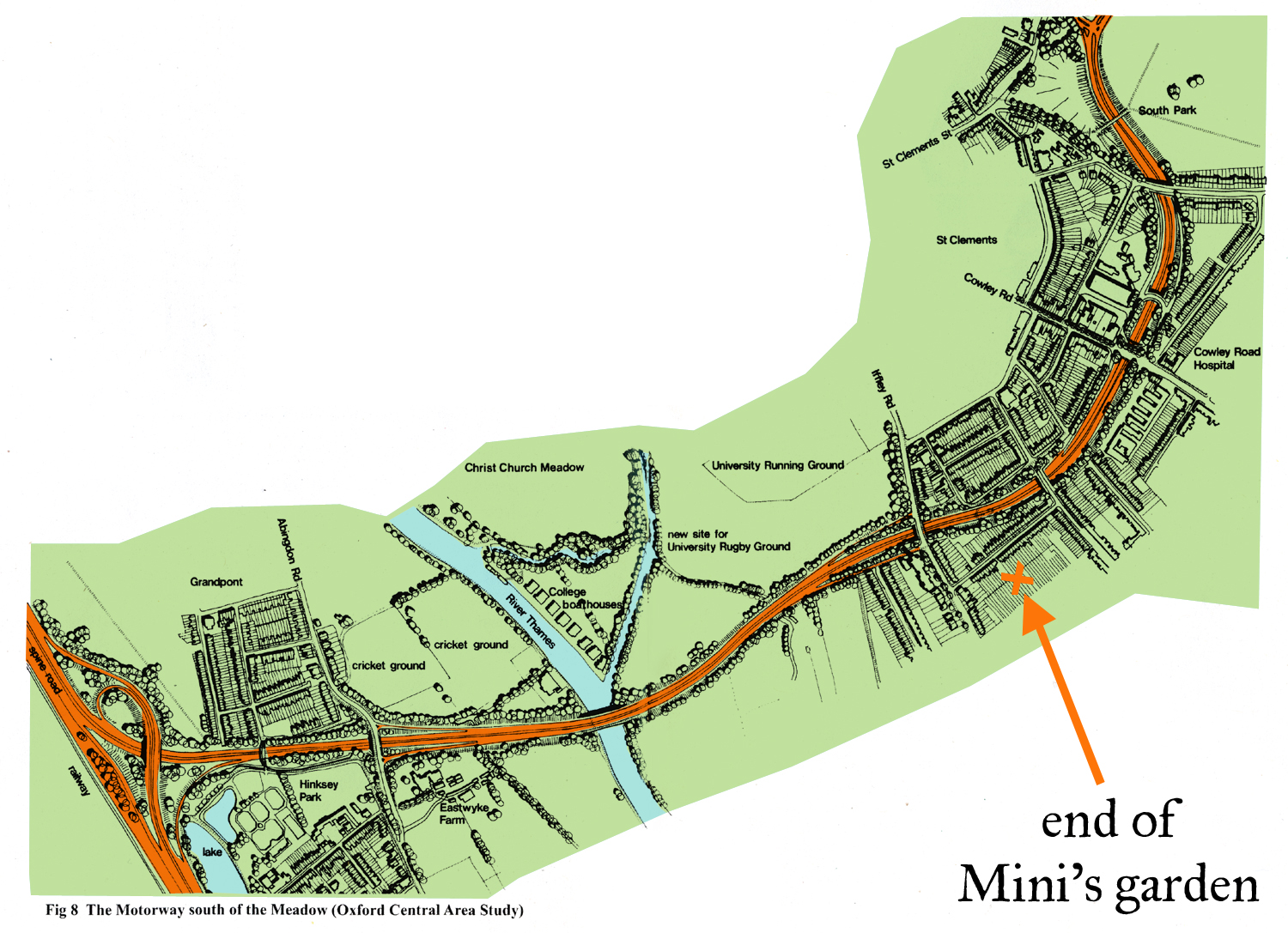

A visualisation of the road-to-be in 1969.

The same spot (I think!) as it is now.

I had a look at where this planned highway would have been.

It would have been just at the bottom of our garden.

A four lane swathe of tarmac cutting through, an impassable barrier for humans and wildlife. I feel a shiver of horror for what could have been.

Planning proposals for an inner relief road hung over Oxford for almost 30 years. You can read more about the whole story here.

Luckily, in 1969, 50 years ago this year, Oxford Civic Society was formed to fight this brutal plan. They won the Battle of the Relief Road, and the planning of Oxford’s roads didn’t go with the needs of the car, but in Park & Rides and pedestrianisation.

Thank you, Oxford Civic Society!

However, Frankenstein’s monster-like, massive road-building plans refuse to stay buried. There’s now the hulking zombie of the proposed Oxford-Cambridge Expressway haunting the future.

Back to the Riverbank

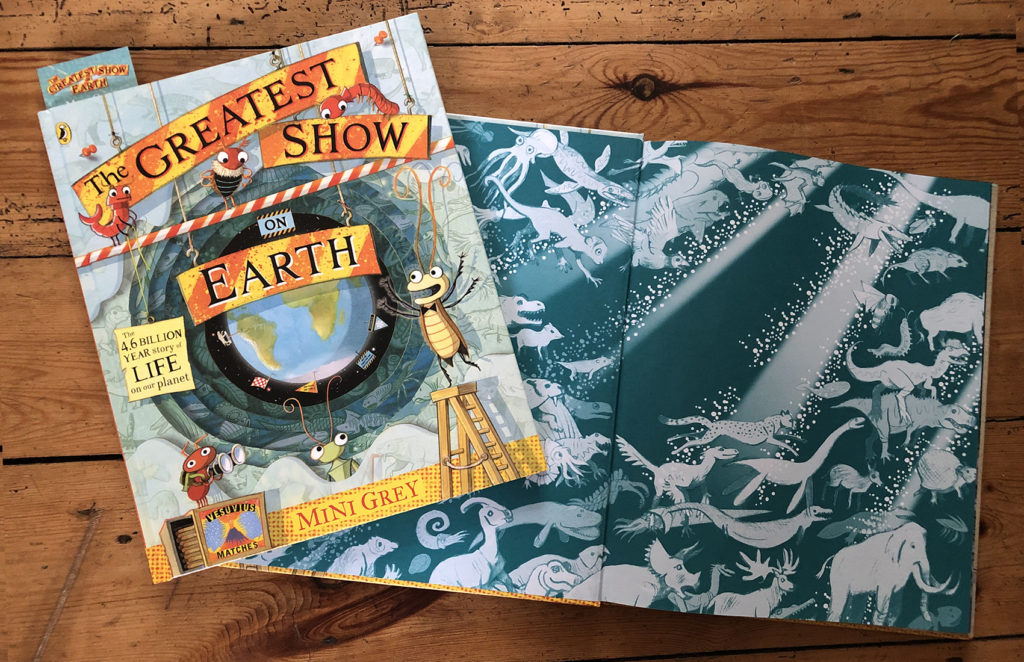

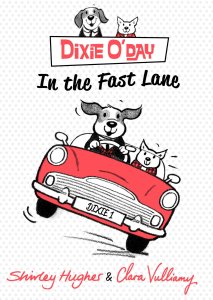

I have recently finished being in the zone of Wind in the Willows.

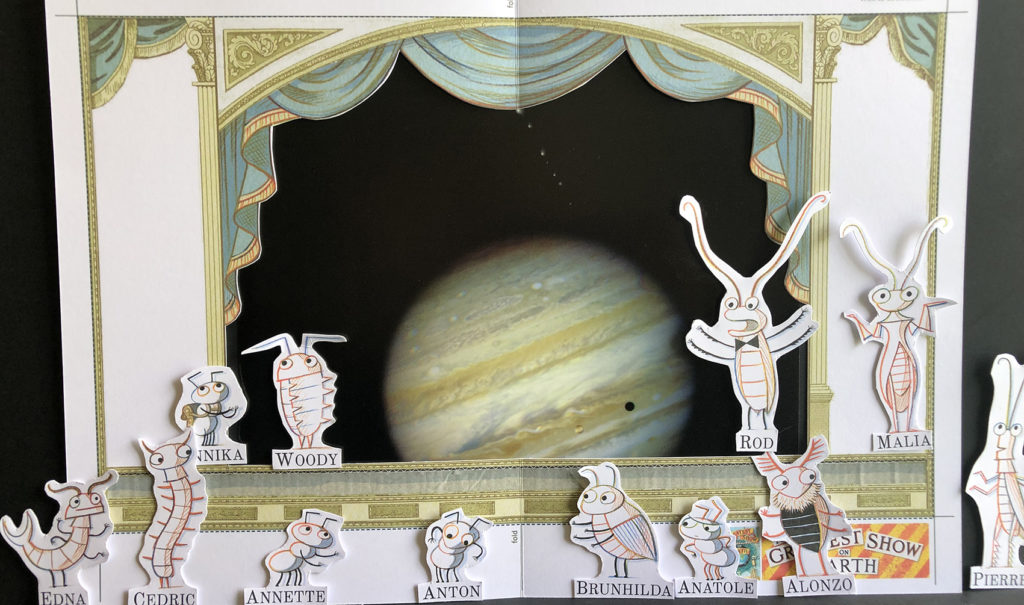

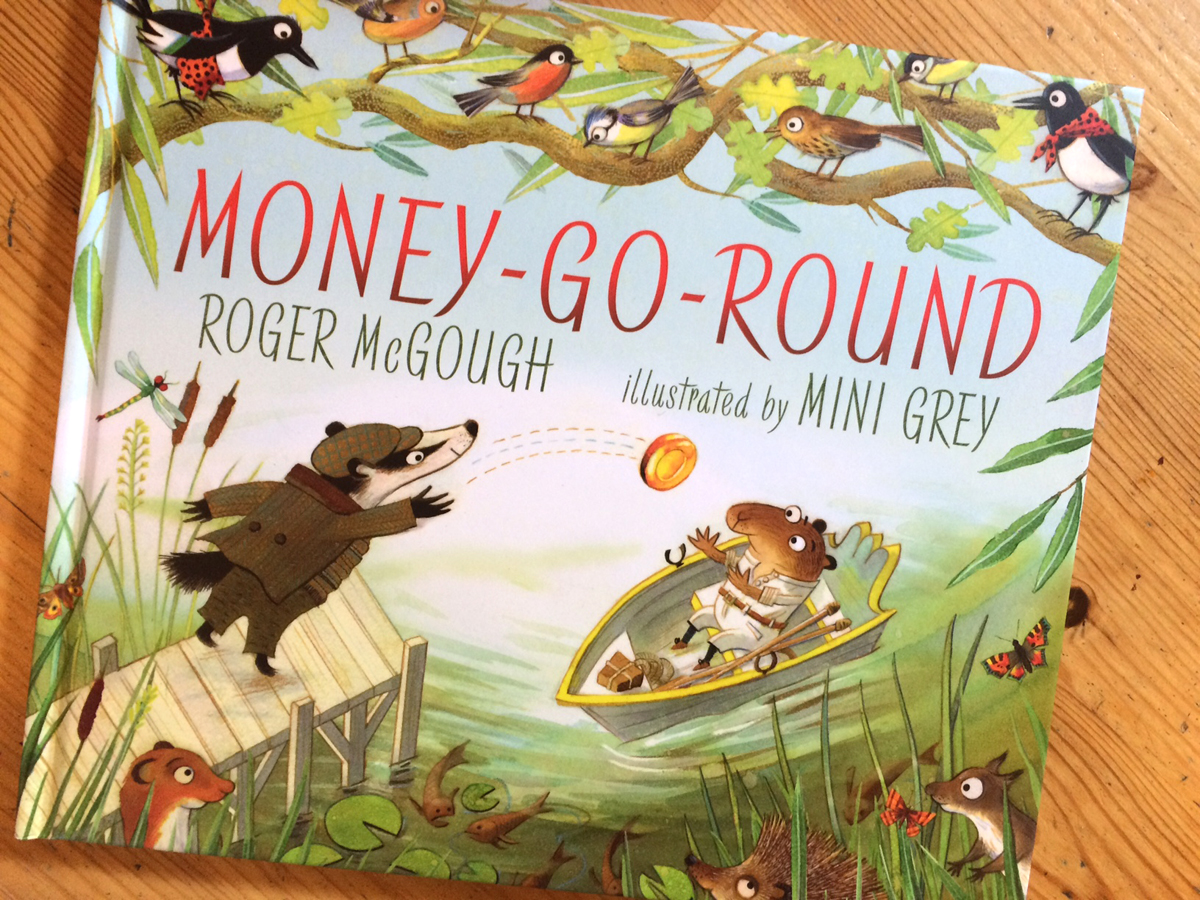

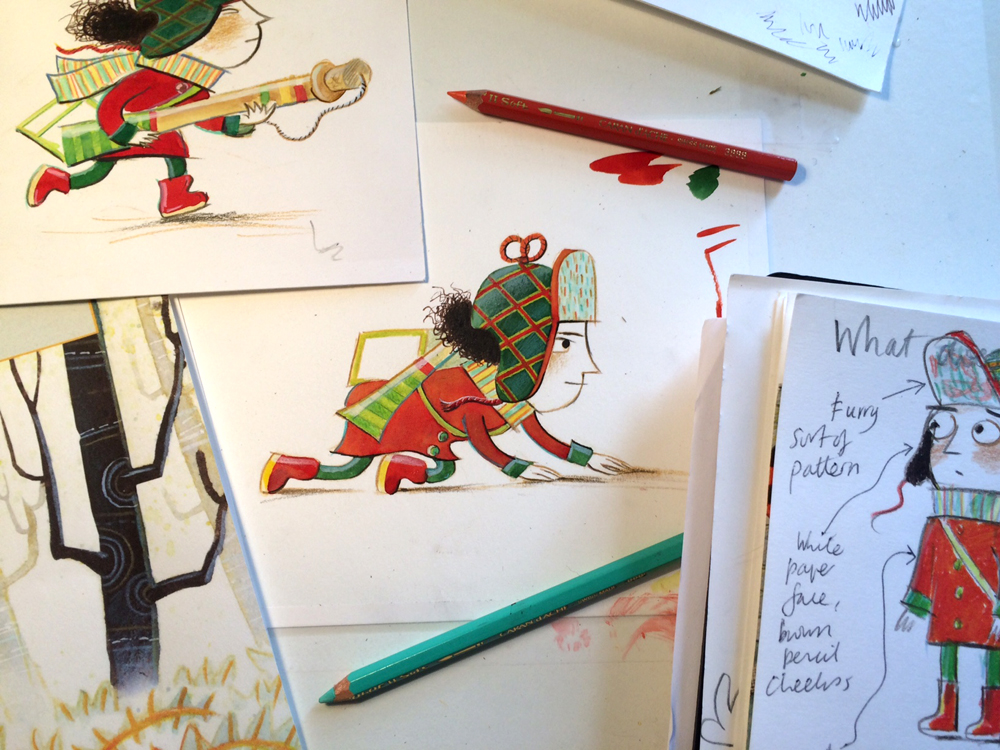

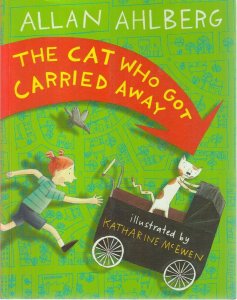

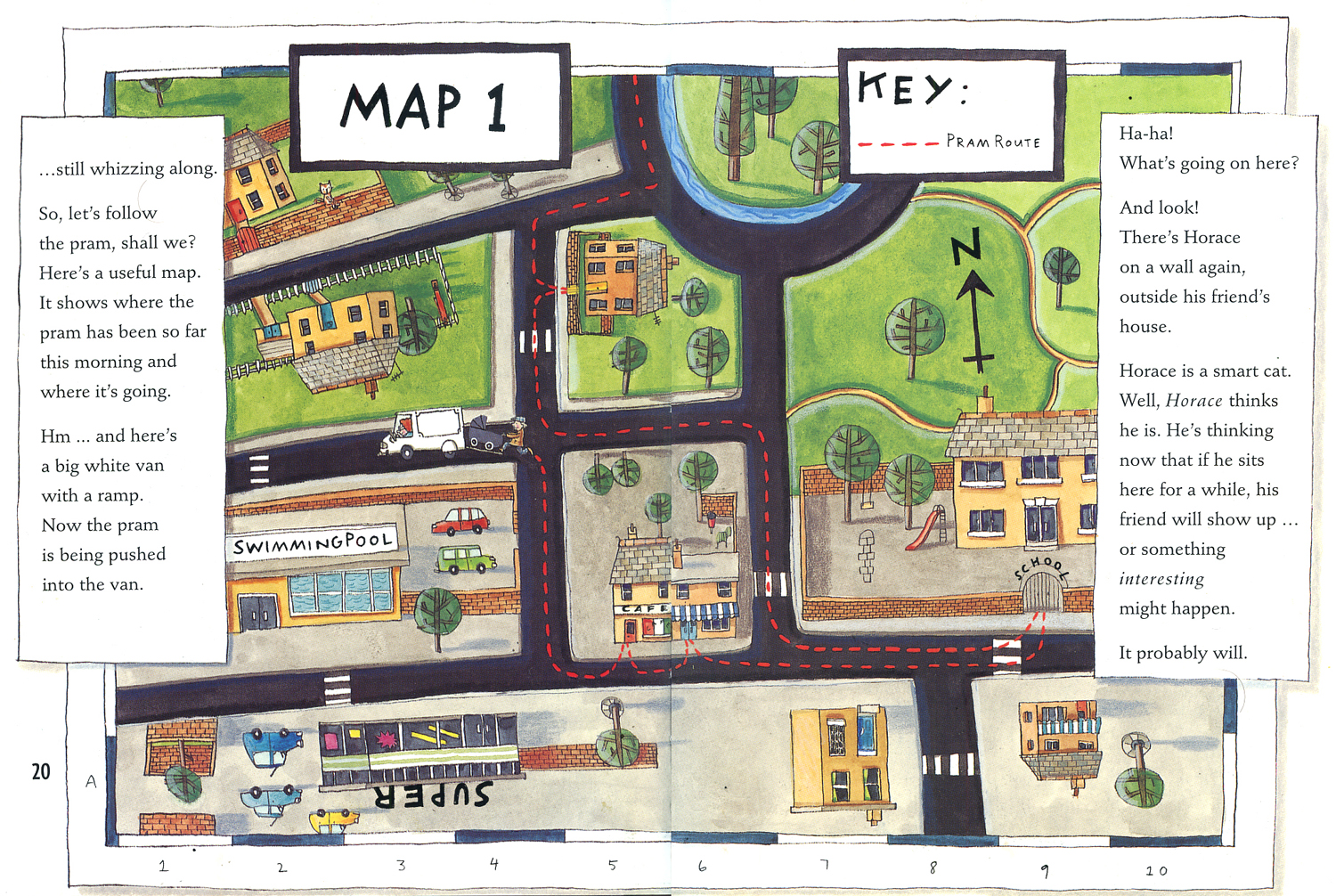

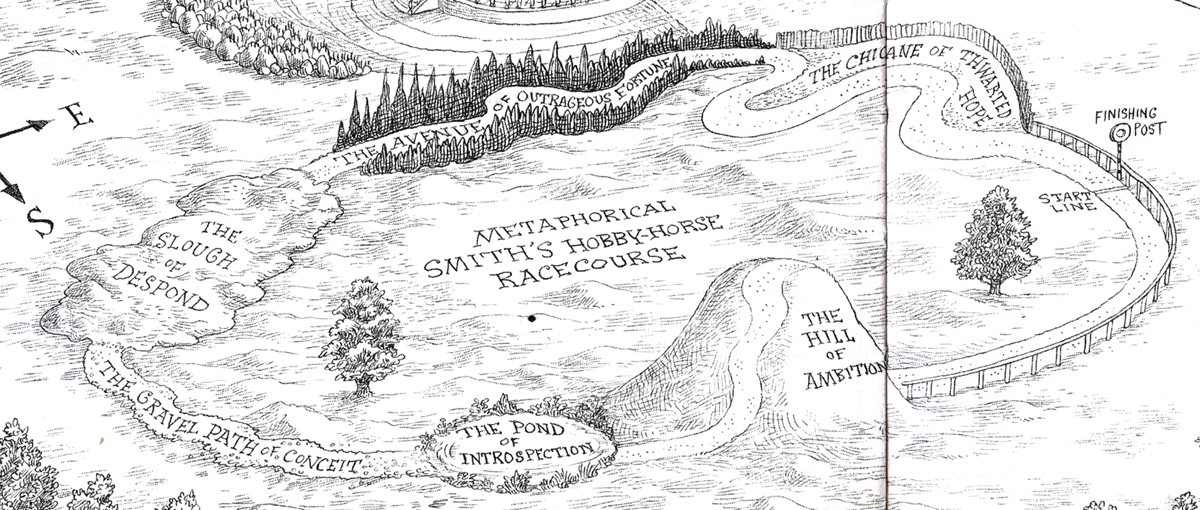

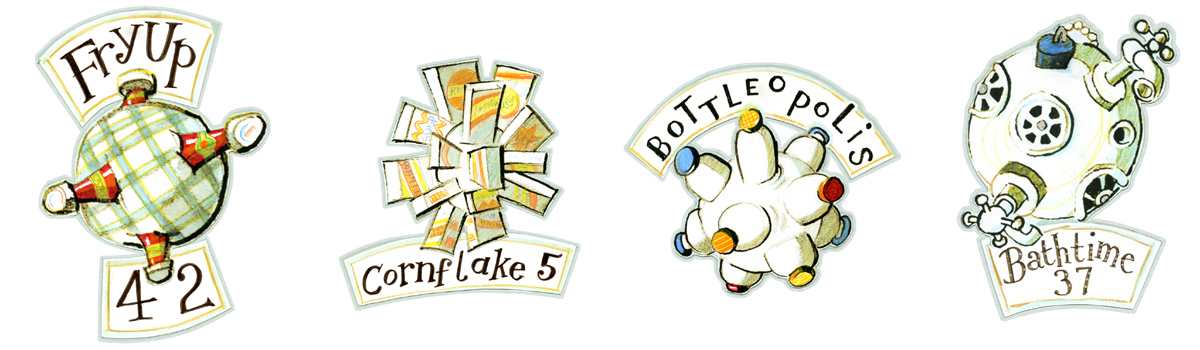

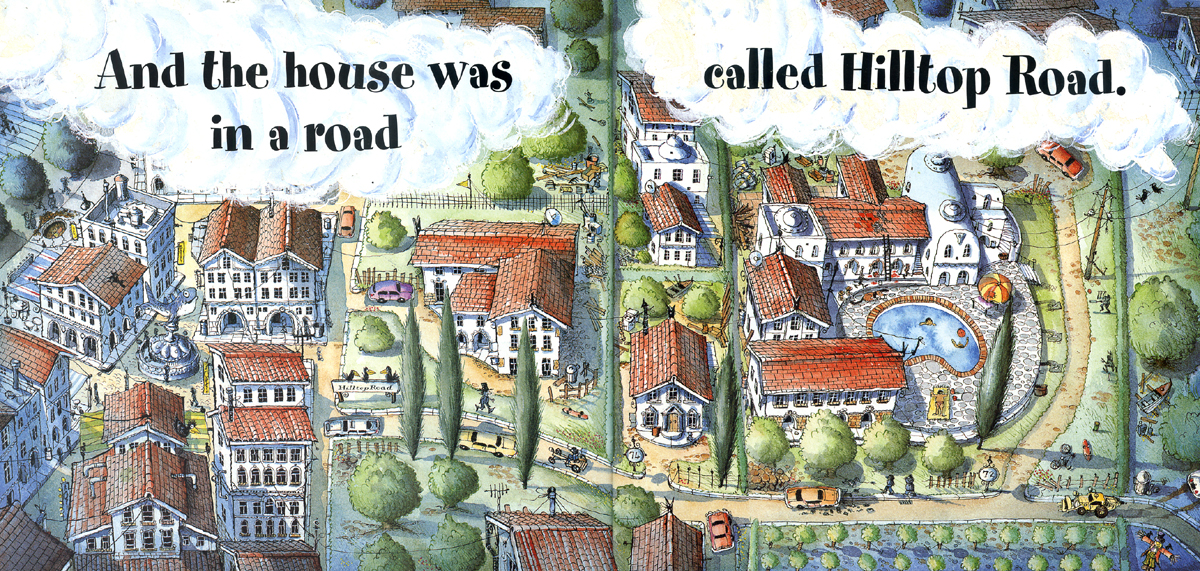

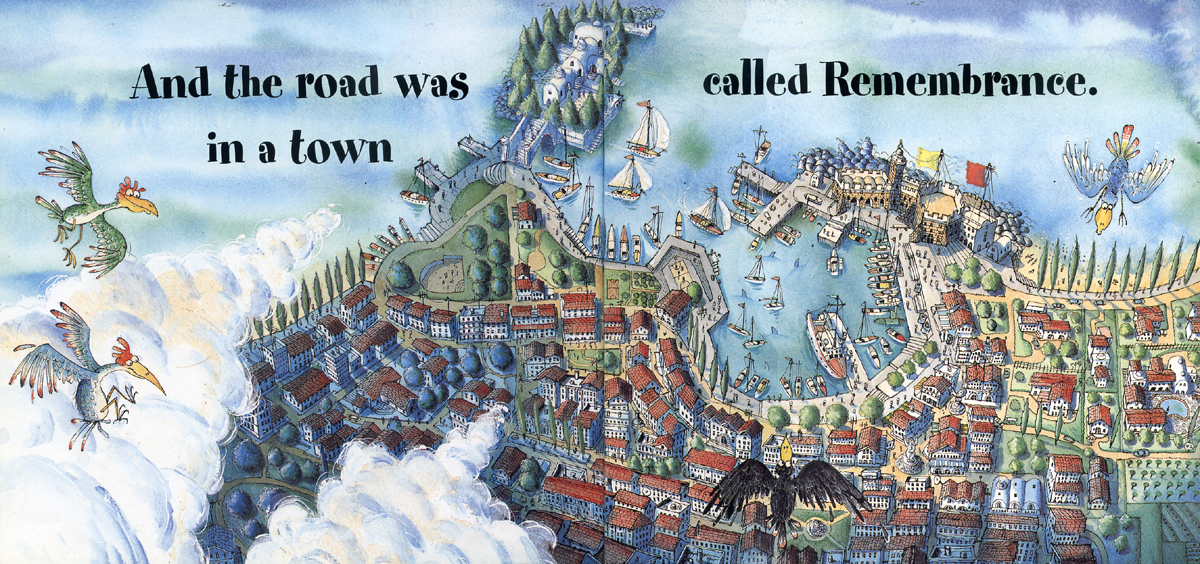

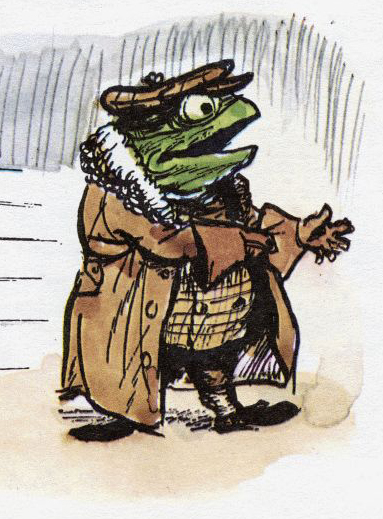

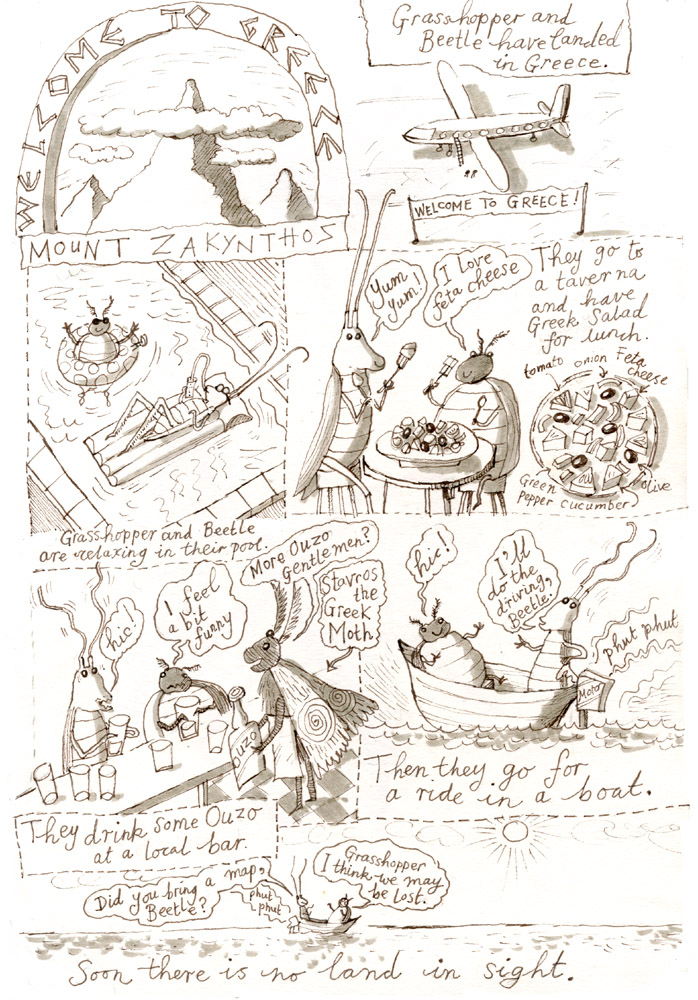

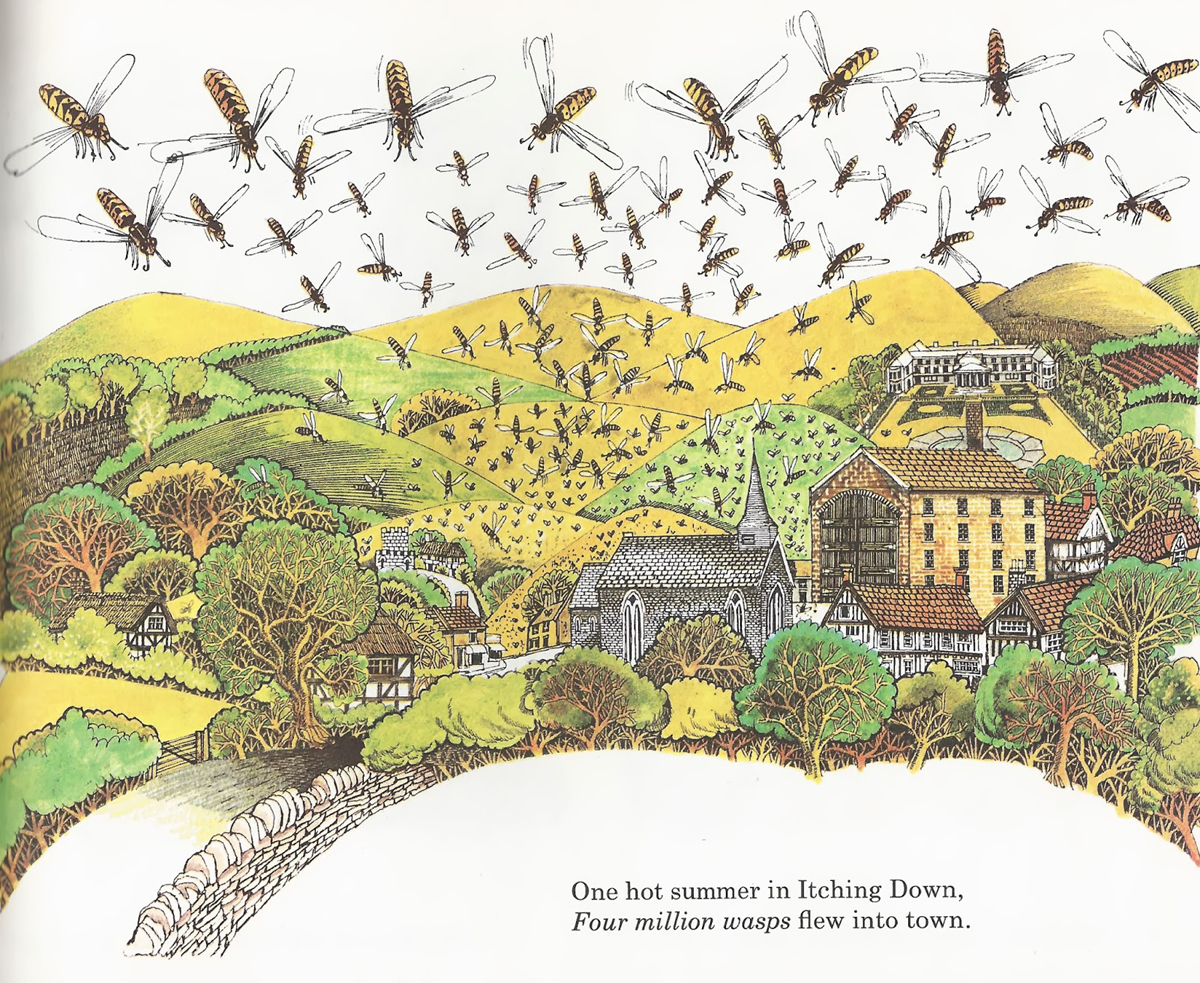

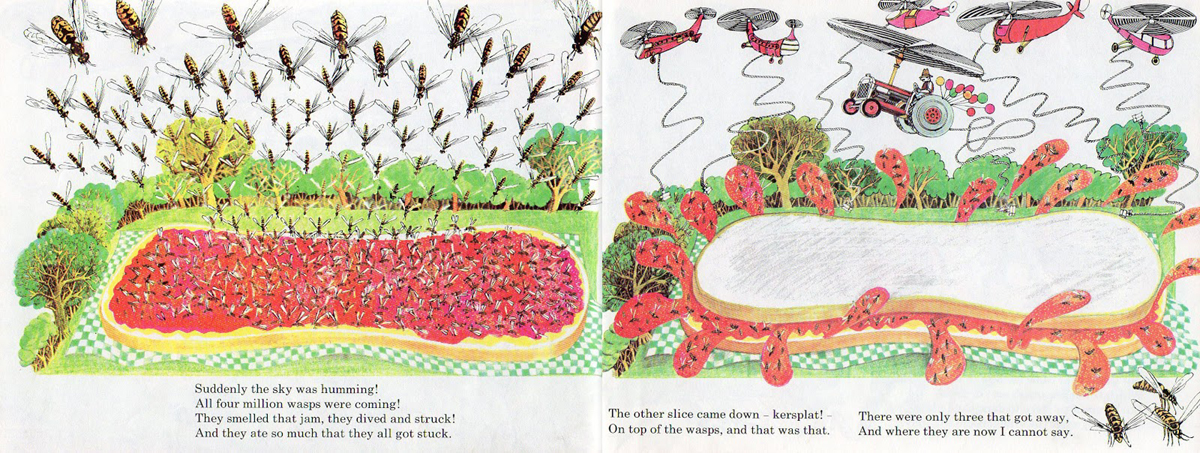

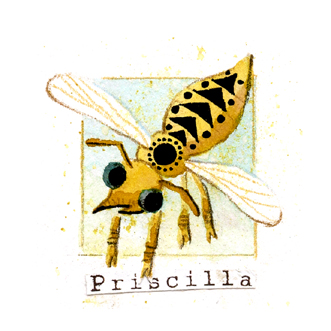

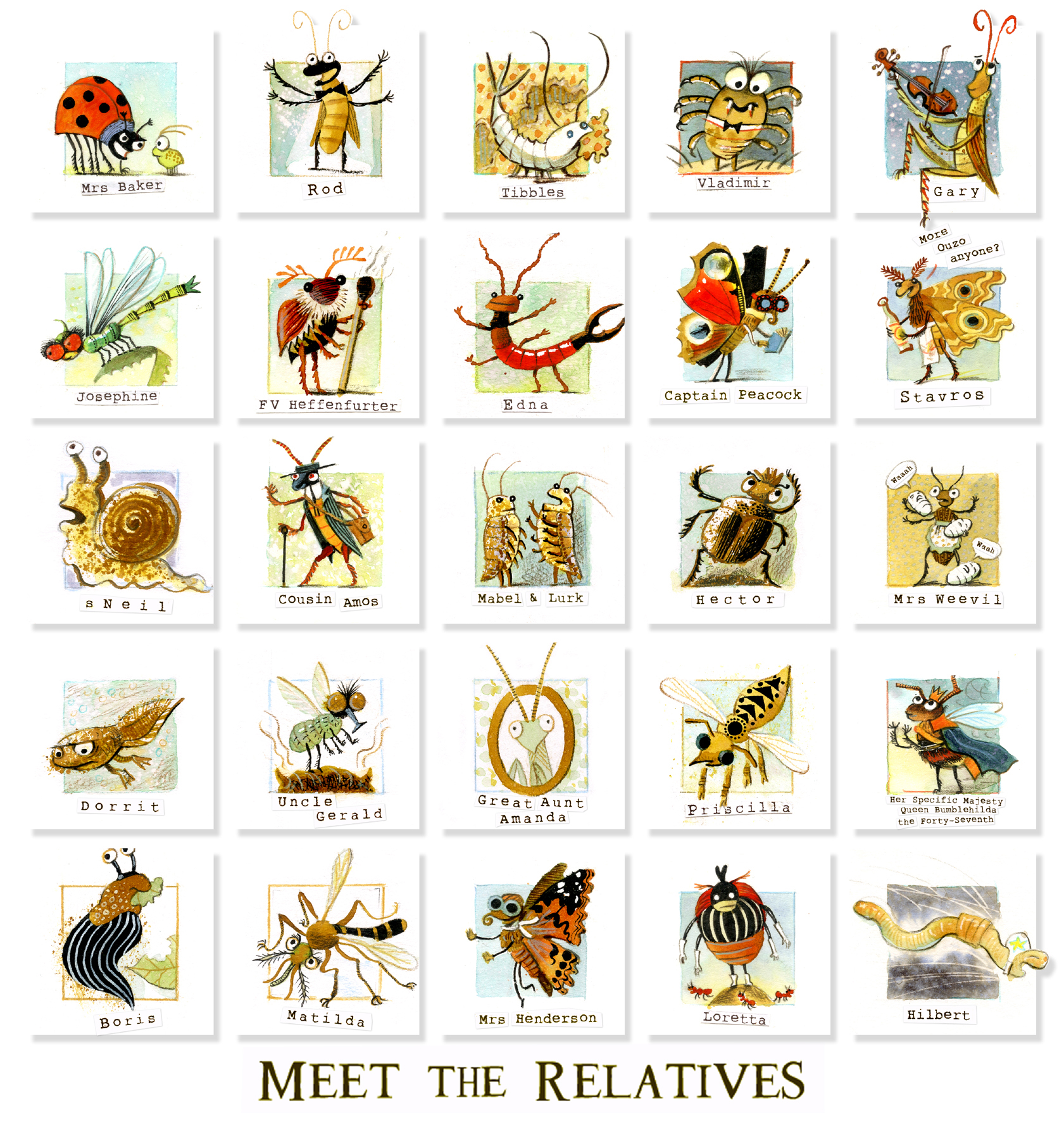

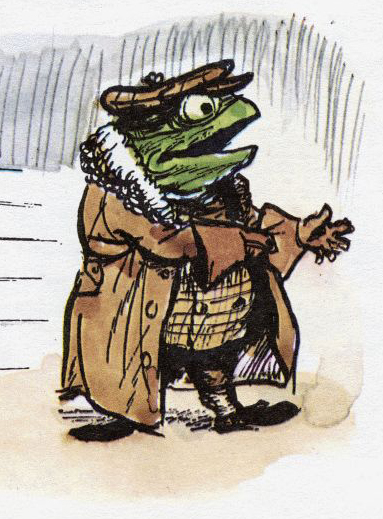

I was illustrating a story by the poet Roger McGough (who has adapted Wind in the Willows for the stage.) The story is called Money Go Round, and is all about the journey of a coin through the paws of all the animals who live along the riverbank – and it starts with the naughty amphibian, Mr Toad.

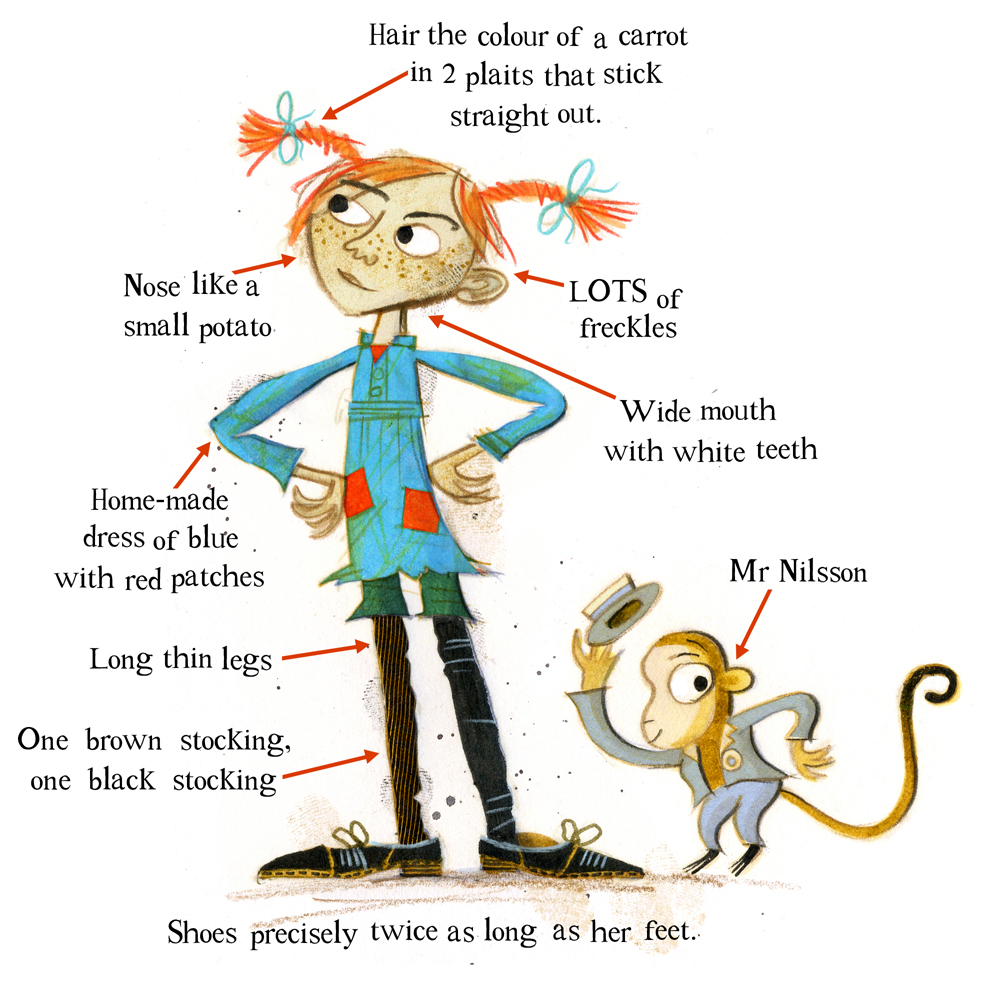

Our mole is female and runs a hotel,

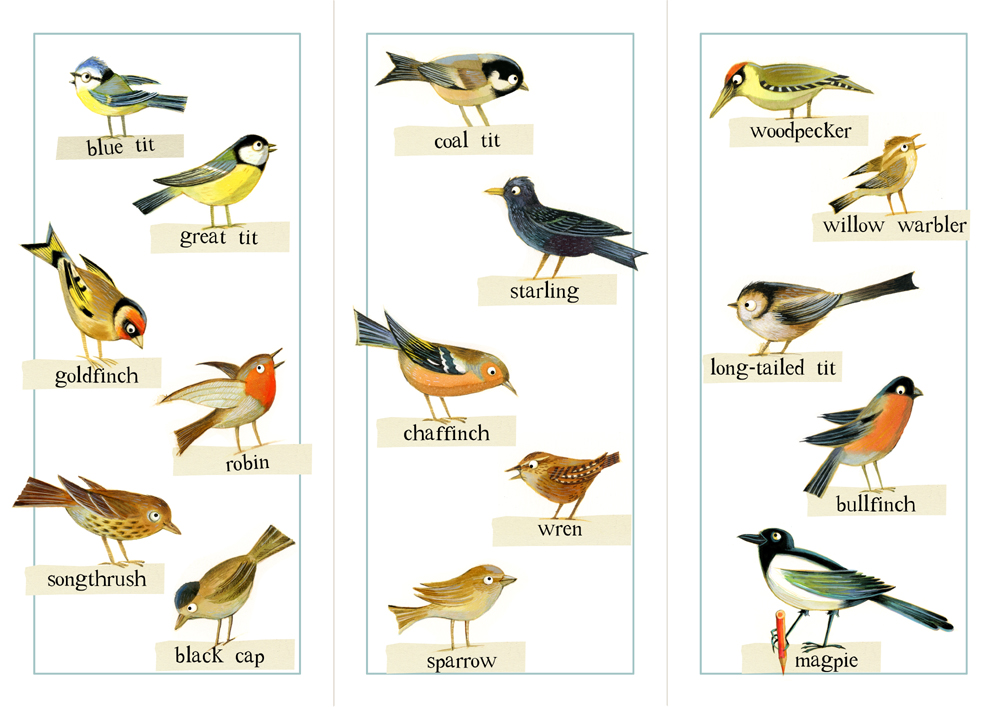

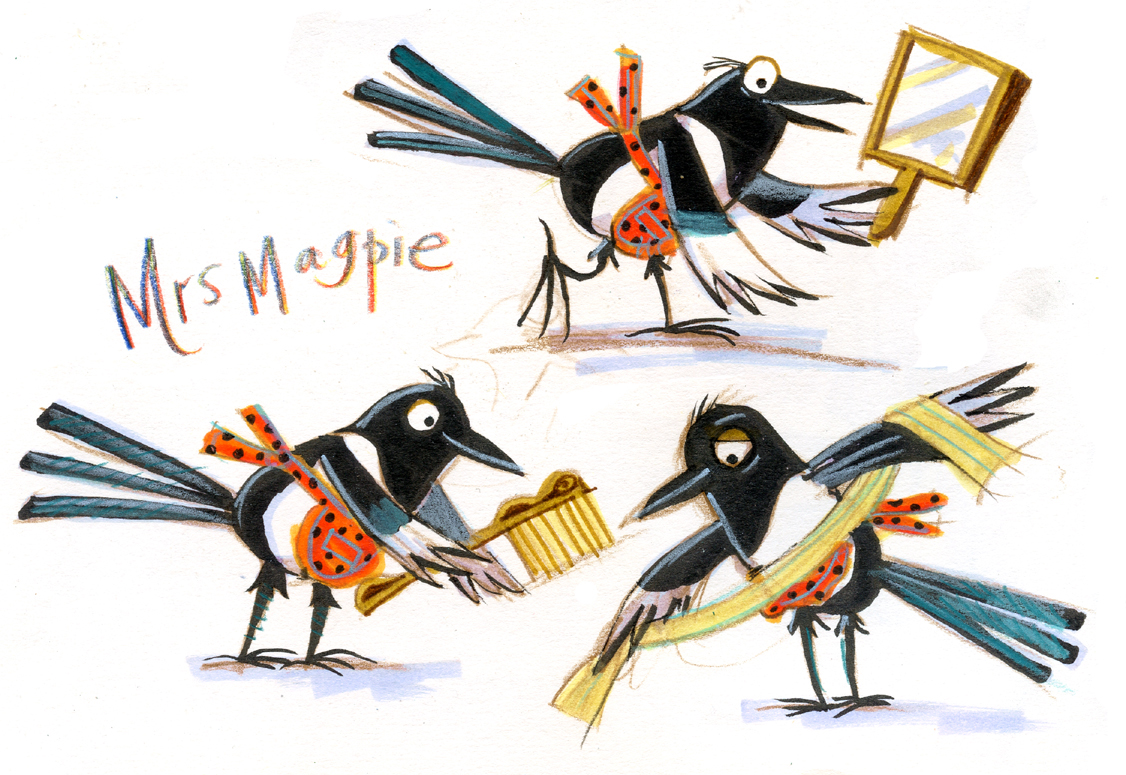

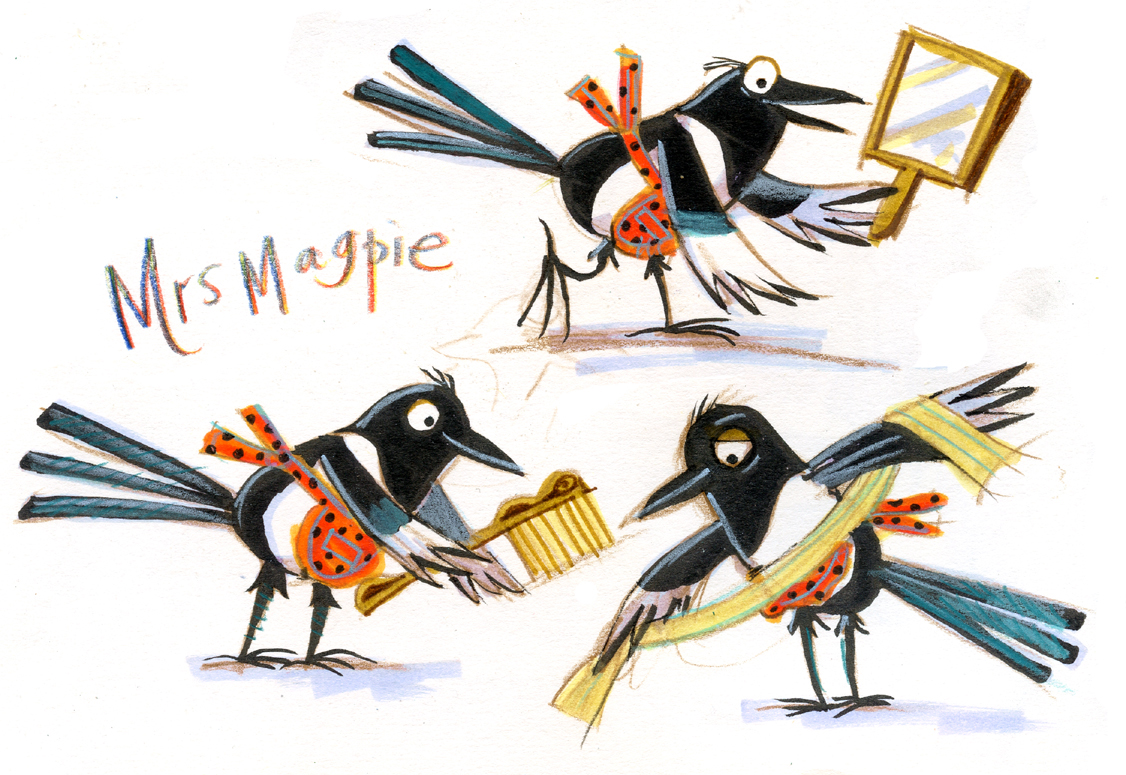

and there’s a painter-decorator stoat, a shack of weasels, and a magpie preening parlour.

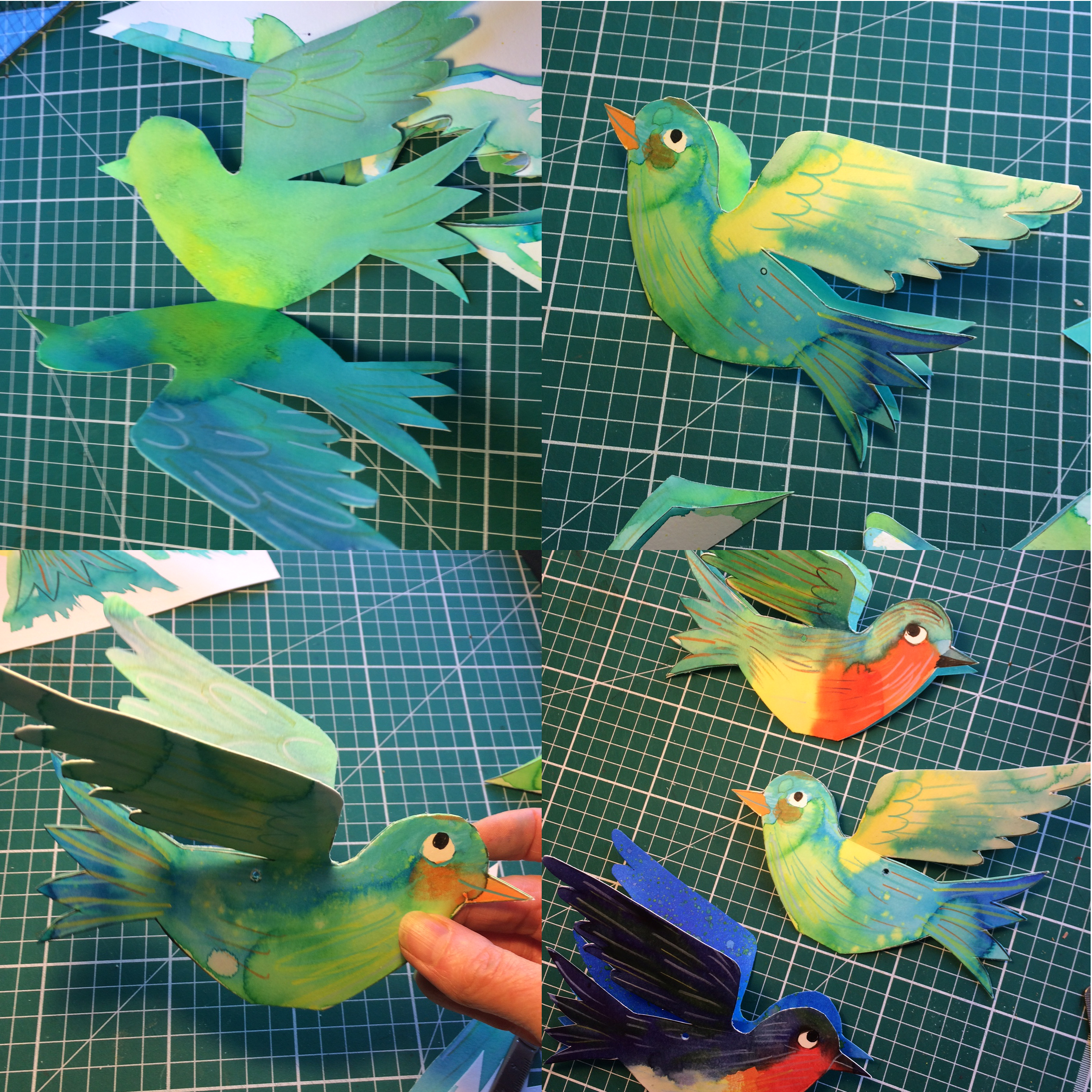

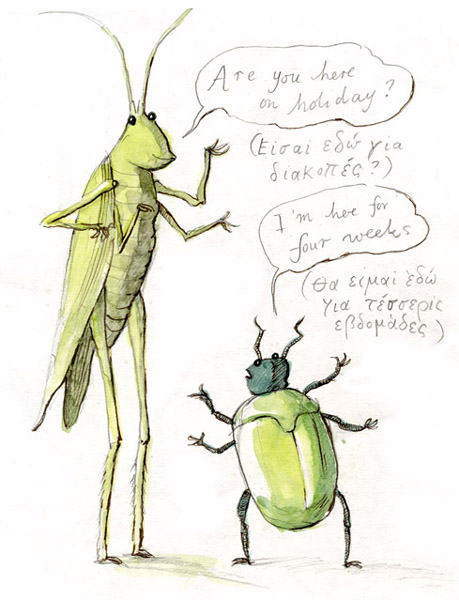

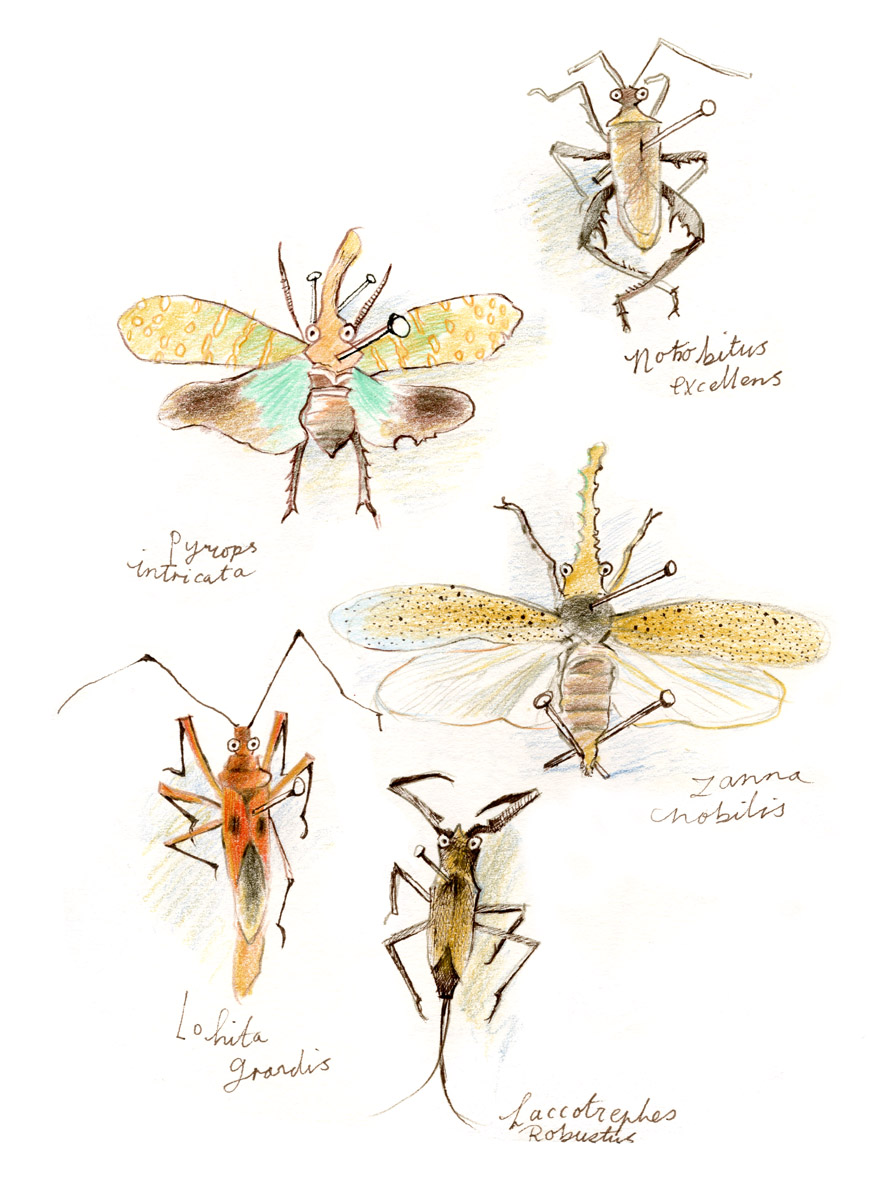

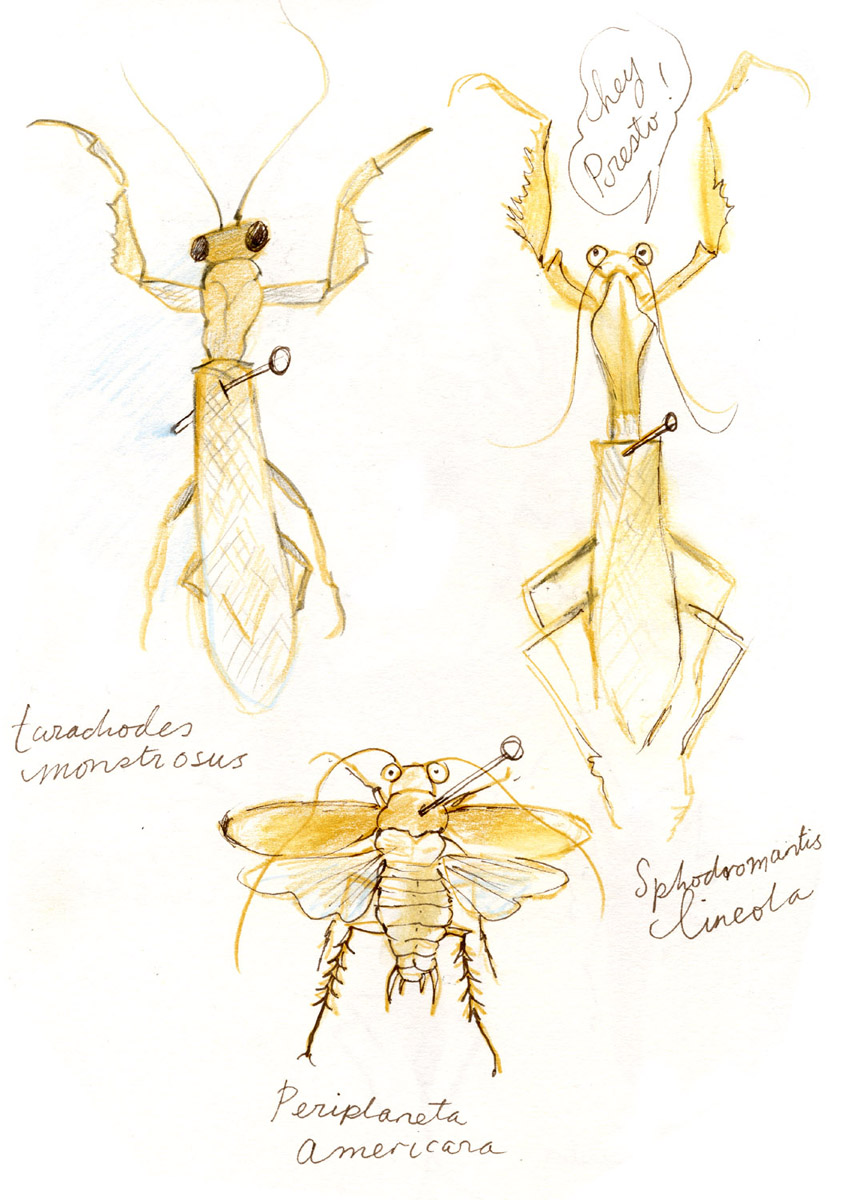

Working out how much to dress the animals was a dilemma I haven’t really had before. Here are character sketches.

Most of all I wanted the river and the willows to flow through the pictures. So, to finish, here’s my favourite character, Walter Rat, in his boat, the Bootle:

Most of all I wanted the river and the willows to flow through the pictures. So, to finish, here’s my favourite character, Walter Rat, in his boat, the Bootle:

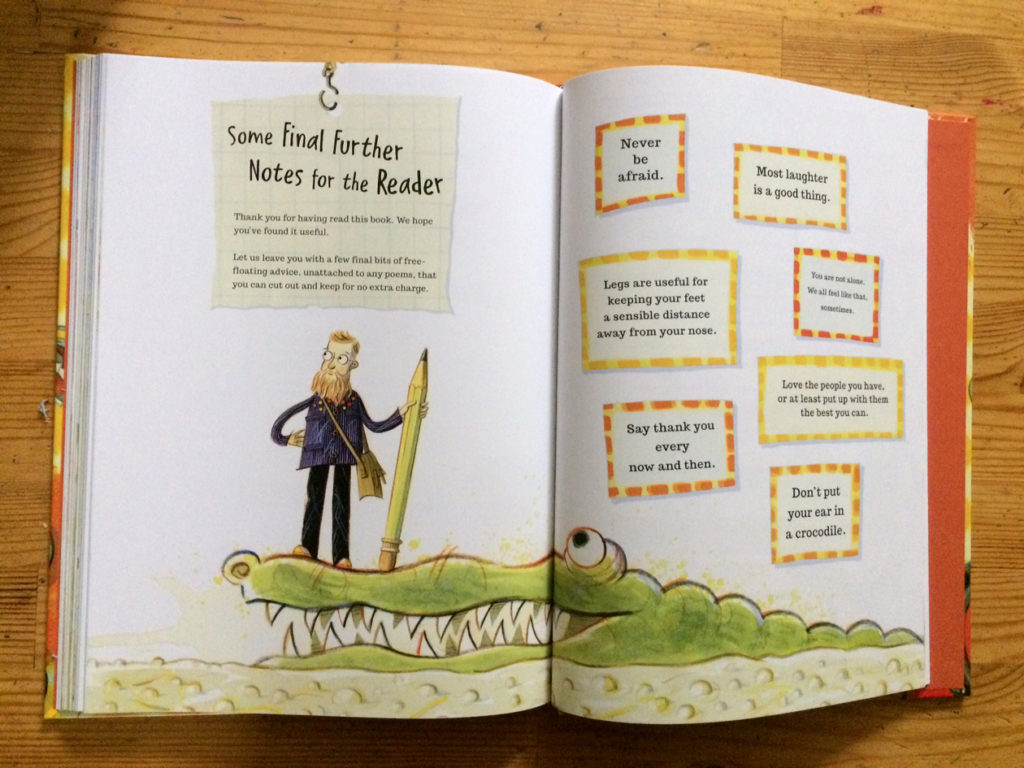

And here’s a PS:

The last picture shows how confused you can get when you are not good at left/right/backwards/forwards. I live near the river and I know you row with your back to where yiu are facing, but I still originally drew Ratty like this:

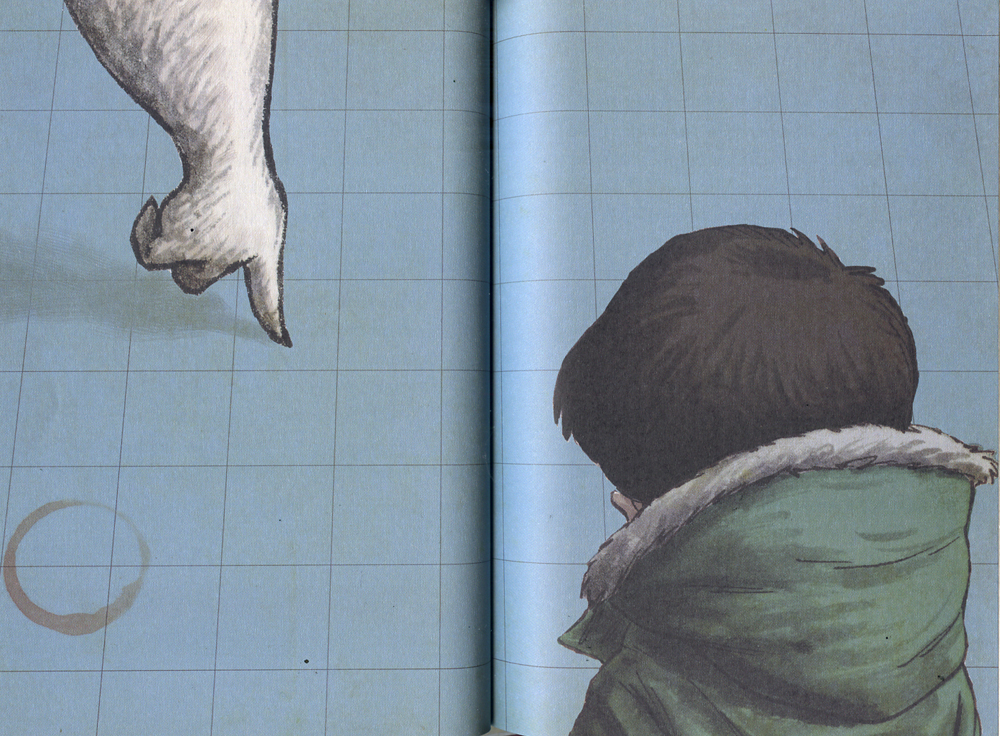

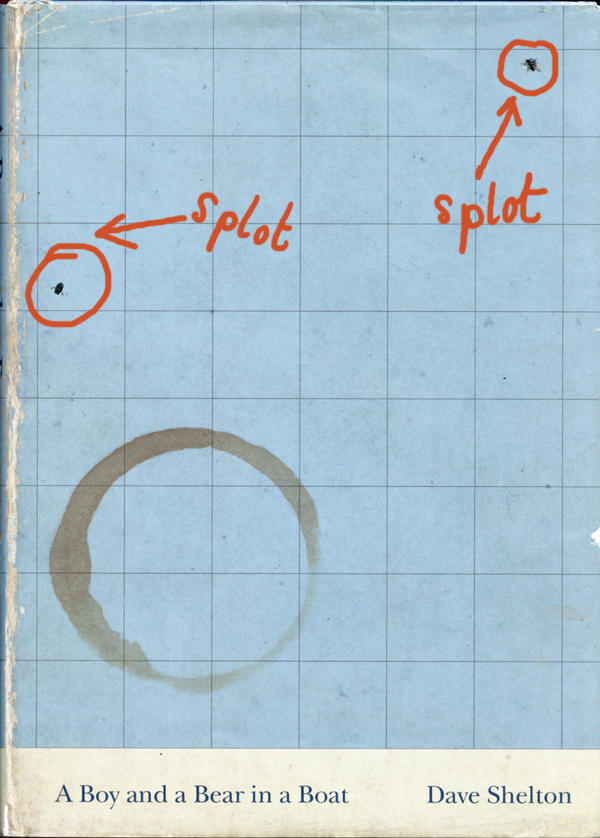

which looks right to me, because I’m thinking Ratty is coming towards me, out of the picture. BUT HE’S NOT!!! So many thanks to the fantastic Dave Shelton for gently pointing this out. And Dave Shelton should know these things, because he is the maker of the marvellous book A Boy, A Bear and a Boat.

which looks right to me, because I’m thinking Ratty is coming towards me, out of the picture. BUT HE’S NOT!!! So many thanks to the fantastic Dave Shelton for gently pointing this out. And Dave Shelton should know these things, because he is the maker of the marvellous book A Boy, A Bear and a Boat.